【Category】Japanese Folktale Series

① The Folktale Story

A long, long time ago, there was a small temple called Shojo-ji in Kisarazu, Chiba Prefecture. The temple was surrounded by mountains, and in the hills lived a large number of Tanuki (Japanese raccoon dogs). Every night, the Tanuki would gather in the temple garden, beat their bellies like drums, making a “Pon-poko, pon!” noise, and regularly played tricks to frighten away and drive out the resident monk (Osho).

First, a highly learned and respectable Osho arrived, but the Tanuki transformed themselves into a one-eyed boy and a Rokurokubi (long-necked woman), frightening him so much that he fled in a single night. Next, a strong and courageous Osho came. He was not intimidated by the shape-shifters and chased the Tanuki around, but the cunning creatures were too quick. The Osho stumbled, suffered a serious injury, and was forced to leave the temple.

The next monk to arrive was a peculiar-looking man in shabby robes. The Tanuki tried their usual tricks, transforming into various monsters to scare him, but this Osho was not frightened at all. Instead, when the Tanuki began their belly drumming, he said, “Oh, this looks interesting,” and started beating his own stomach.

As the Tanuki beat “Pon-poko, pon!”, the Osho struck his belly back, “Don-tsuku, don!” determined not to be outdone. However, the Osho beat his stomach so hard that he collapsed and lost consciousness.

Alarmed, the Tanuki thought, “Did we go too far?” They quickly nursed the Osho and carried him into the temple’s main hall.

The next day, the Osho, undeterred, began practicing his belly drumming again. Hearing the sound, the Tanuki returned to the temple.

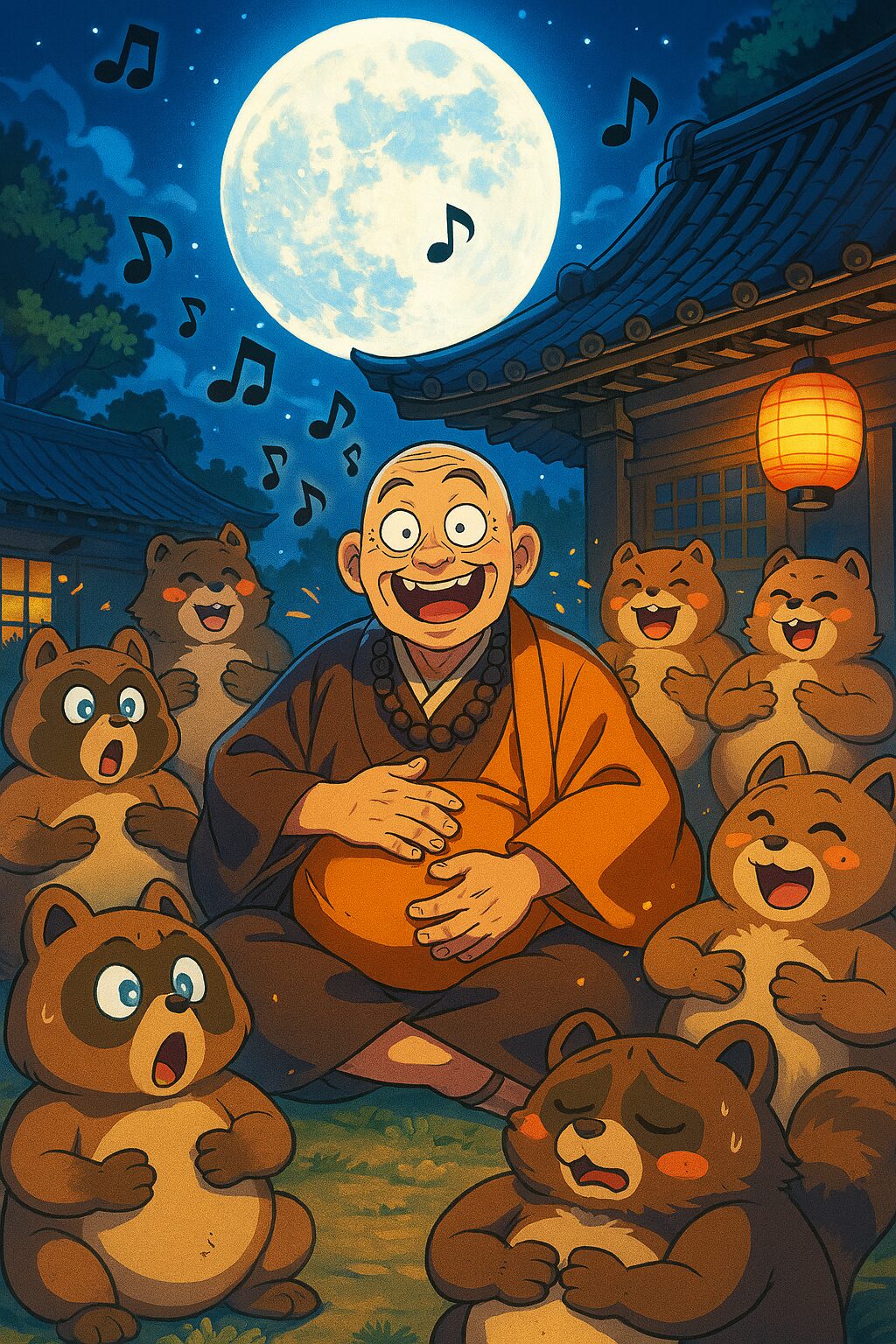

On a night of the full moon, the Osho and the Tanuki began their grand belly-drumming contest. The Osho was much better than the day before, and his drumming was light and wonderful. The Tanuki Boss, determined not to lose face, put all his strength into it and continued to beat his belly with fervent dedication.

However, with a final “Pon!” from the Boss’s belly drum, the Boss winced in pain and hunched over. Shockingly, his belly had ruptured from beating it too hard.

The Osho, far from celebrating his victory, immediately went to fetch medicinal herbs. He carefully applied the medicine to the Boss’s ruptured belly and nursed him back to health with the utmost care.

The Boss Tanuki was deeply surprised and profoundly grateful that his drumming rival was an Osho with such a kind heart.

Since this event, the Tanuki stopped playing tricks on the Osho. On the contrary, the Osho and the Tanuki became great friends. It is said that on nights of the full moon, they would gather in the garden, beating their belly drums and enjoying the moon-viewing banquet together.

② Analysis of the Folktale

“Shojoji no Tanukibayashi” might seem like just a humorous and comical animal tale at first glance. However, at its core, it is deeply infused with the unique philosophy found in Japanese folktales.

The most striking feature of this story is how **a structure of conflict with “the different” is ultimately transformed into “coexistence.”**

First, let’s look at the first two monks who came to the temple:

- The Learned Osho: He perceived the Tanuki as “alien beings to be feared” based on his knowledge and status. His attitude was one of exclusion, and as a result, he was driven out. This highlights the limits of judging different cultures or beings solely through fixed notions or pure reason.

- The Courageous Osho: He viewed the Tanuki as “enemies to be conquered” using physical force. However, he couldn’t cope with the “cunning” side of the Tanuki, suggesting that reliance on brute force alone is insufficient for resolution.

The **peculiar Osho** who arrived third is the true protagonist of the story. He reacted to the Tanuki’s belly drumming by saying, “This looks interesting,” and participated himself, demonstrating an attitude of **”acceptance and participation.”** Instead of fearing or eliminating the Tanuki, he accepted their culture and behavior—in this case, **”play”**—and attempted to assimilate.

The Osho’s action is a profound display of Japanese flexibility and tolerance: not “defeating” the opposing force, but **”assimilating and enjoying it together.”**

Ultimately, when the Tanuki Boss ruptured his stomach, the Osho did not claim victory but instead showed an act of compassion by “helping.” This single act fundamentally changed the relationship between human and animal, establishing a foundation of trust and friendship.

In essence, this folktale conveys the universal lesson that **true strength is not the physical power to defeat an opponent, but the spiritual tolerance to accept the different and treat them with compassion.** The story reflects the Japanese spirit of respect for nature and different cultures, and the emphasis on harmony, nurtured over the nation’s long history.

③ Cultural Connection: What We Can Learn from the Folktale

“Shojoji no Tanukibayashi” is not just a fairy tale; it is deeply connected to the unique values that the Japanese people have cultivated through their interaction with nature and society. The cultural connections that can be drawn from this folktale primarily boil down to two points:

1. Coexistence with Nature: The Spirit of **”Animism”**

The foundation of Japanese culture lies in the **Animistic** belief that gods or spirits (tamashii) reside in all things in the natural world. Animals like the Tanuki (raccoon dog) and Kitsune (fox) have been perceived not just as beasts, but as **”shape-shifters”** with powers beyond human comprehension, or even as **”divine messengers (shinshi).”**

In this story, the Tanuki are both mischievous antagonists who trouble humans and humorous “performers.” The Osho’s acceptance of their “belly drumming” — without fear — signifies the choice to **not eliminate the forces of nature, but to accept their energy as “liveliness” and “fun,” and to coexist.** This reflects the Japanese view of nature, where people have lived by accepting both the blessings and the disasters of the natural world, particularly through their agricultural culture. The philosophy here is that even a fearsome existence can become an object of harmony when treated with respect.

2. Societal Norms and Flexibility Emphasizing **”Wa” (Harmony)**

The most crucial lesson from this folktale is the spirit of **”Wa o motte toutoshi to nasu” (Harmony is to be valued)**, a foundational principle of Japan.

The Osho “fought” the Tanuki through a belly-drumming contest, but it was not a fight to destroy the opponent. Rather, it was a kind of ritualistic competition to **”enter the opponent’s turf and perform to the best of one’s ability within the rules.”** Ultimately, true “Wa” is achieved through the **”Compassion”** of helping the injured opponent, transcending the outcome of the contest.

In Japanese society, flexibility to first accept the other is valued, aiming to avoid direct confrontation or conflict. The ending, where the Osho’s display of **humor and tolerance towards the different leads to them “becoming friends,”** depicts an ideal process for overcoming conflict and creating harmony in a diverse collective, which is highly valued in Japan.

For international readers, this story serves as a key to understanding a profound cultural aspect: **that for the Japanese, strength is born not from domination, but from acceptance and compassion.**

④ Concluding with a Question to the Reader

Now that you have read the tale of “Shojoji no Tanukibayashi,” what are your thoughts?

If you were the first learned Osho or the courageous Osho who came to the temple, what actions would you have taken to drive out the Tanuki? Perhaps in our modern times, we might employ scientific methods or more pragmatic means.

However, the eccentric Osho chose the most humorous and perhaps riskiest method: **”joining in the opponent’s game.”** He understood the opponent’s intention, and instead of denying their behavior, he participated in the unusual act of “belly drumming,” thereby breaking the structure of conflict and building a relationship of trust.

What is the “alien presence” in your life? It might be a cultural difference, or a clash of values.

Faced with that which is different or difficult, would you choose the path of **”exclusion through fear or force,”** or like this Osho, would you seek **”a path to enjoy together with curiosity and tolerance”?**

I hope this story provides a chance for you to think deeply about your daily relationships and how you approach cultural differences.

⑤ External Links and Category

【Category】

Japanese Folktale Series

【External Links】

- Shojo-ji Temple Official Website (Japanese):

The temple in Kisarazu, Chiba Prefecture, that is the setting of this folktale. Feel the history behind the legend.

https://shojoji.net/ - Doyo (Children’s Song) “Shojoji no Tanukibayashi” (Wikipedia – Japanese):

An explanation of the very famous Japanese children’s song inspired by this folktale.

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%A8%BC%E5%9F%8E%E5%AF%BA%E3%81%AE%E7%8B%B8%E5%9B%83%E5%AD%90

日本のユーモアと寛容の心:「しょじょ寺の狸林(しょうじょうじのたぬきばやし)」が語る共生の物語

日本のユーモアと寛容の心:「しょじょ寺の狸林(しょうじょうじのたぬきばやし)」が語る共生の物語

【カテゴリー】Japanese Folktale Series

①昔話のストーリー

むかしむかし、千葉県の木更津(きさらづ)に、証誠寺(しょうじょうじ)という小さなお寺がありました。この寺は山に囲まれ、その裏山にはたくさんの狸(たぬき)が棲んでいました。狸たちは夜になると、寺の庭に集まっては腹鼓(はらつづみ)を打ち、「ぽんぽこ、ぽん!」と騒ぎ立て、ついには和尚(おしょう)さんを化かして追い出すのが日課となっていました。

最初は学識高い立派な和尚さんが来ましたが、一つ目小僧やろくろ首に化けた狸のいたずらに恐れをなし、一晩で逃げ出してしまいました。次に、力自慢の豪傑(ごうけつ)和尚がやってきました。彼は化け物にも動じず、狸を追いかけ回しましたが、狡猾(こうかつ)な狸たちは素早く、和尚はつまずいて大怪我をしてしまい、やむなく寺を去りました。

次に寺へやってきたのは、何ともみすぼらしい格好をした、風変わりな和尚さんでした。狸たちはいつものように和尚を驚かそうと様々な化け物に姿を変えましたが、この和尚さんは少しも怖がりません。それどころか、狸たちが腹鼓を打ち始めると、「ほう、これは面白そうじゃ」と言って、自分もお腹を叩き始めました。

「ぽんぽこ、ぽん!」と狸たちが叩けば、和尚さんも負けじと「どんつく、どん!」と腹を叩きます。しかし、和尚さんはあまりにお腹を叩きすぎたせいで、倒れて気を失ってしまいました。

狸たちは「やりすぎたか」と慌て、和尚を介抱して寺の本堂へ運び入れました。

翌日、和尚さんは懲りずに腹鼓の練習を始めます。その音を聞きつけた狸たちが、また寺へ集まってきました。

満月の夜、和尚さんと狸たちの腹鼓合戦が始まりました。和尚さんは昨日よりもさらに上手になっており、腹鼓の音は軽快で素晴らしいものでした。狸の親分は面子(めんつ)にかけて負けるわけにはいかないと、力いっぱい、夢中になって腹を叩き続けました。

ところが、「ぽん!」という親分の腹鼓の音とともに、親分は苦しそうにうずくまってしまいました。なんと、腹を叩きすぎたせいで、お腹が破れてしまったのです。

これを見た和尚さんは、勝ったと喜ぶどころか、すぐに薬草を取りに行き、親分の破れたお腹に丁寧に塗り、手厚く看病してやりました。

親分狸は、自分の腹鼓合戦の相手が、こんなにも優しい心を持った和尚だったことに心底驚き、深く感謝しました。

この一件以来、狸たちは和尚さんにいたずらをすることを止めました。それどころか、和尚さんと狸たちはすっかり仲良くなり、満月の夜には腹鼓を打ち鳴らしながら、一緒に月見の宴を楽しむようになったということです。

②昔話を考察する記事

「しょじょ寺の狸林」は、一見すると滑稽(こっけい)でコミカルな動物譚(どうぶつたん)に過ぎないかもしれません。しかし、その根底には、日本の昔話が持つ特有の哲学が深く息づいています。

この物語の最大の特徴は、「異質なもの」との対立構造が、最終的に「共生」へと転換する点です。

まず、寺にやってきた最初の二人の和尚を見てみましょう。

- 学識高い和尚: 彼は知識や身分によって狸を「恐れるべき異物」と認識しました。彼の態度は排他的であり、結果として寺から追い出されます。これは、固定観念や理性のみで異文化や異質な存在を判断することの限界を示しています。

- 豪傑和尚: 彼は力という物理的な手段で狸を「征服すべき敵」と見なしました。しかし、彼は狸の「ずる賢さ」という別の側面に対応できず、力に頼るだけでは解決できないことを示唆しています。

そして、三番目に現れた風変わりな和尚さんこそが、物語の真の主人公です。彼は、狸の腹鼓に対して「面白そうじゃ」と反応し、自らも参加するという「受容と参加」の姿勢を示しました。彼は狸を恐れたり、排除したりするのではなく、彼らの文化や行動様式を「遊び」として受け入れ、同化しようと試みたのです。

この和尚の行動は、対立するものを「打ち負かす」のではなく、「同化し、共に楽しむ」という、きわめて日本的な柔軟性と寛容さの表れです。

究極的には、狸の親分が腹を破裂させた際、和尚は勝利を宣言するのではなく、「助ける」という慈悲の行動に出ます。この行為が、これまで対立していた人間と動物の関係を決定的に変化させ、信頼と友情の基盤を築きました。

つまり、この昔話は、真の強さとは、相手を打ち負かす物理的な力ではなく、異質なものを受け入れ、慈悲をもって接する精神的な寛容さであるという、普遍的な教訓を私たちに示しているのです。この物語は、日本の長い歴史の中で育まれた、自然や異文化への敬意と、調和を重んじる精神構造を反映していると言えるでしょう。

③昔話から読み解く日本文化との関連

「しょじょ寺の狸林」は、単なるおとぎ話としてではなく、日本人が自然や社会との関わりの中で培ってきた独特な価値観と深く結びついています。この昔話から読み解ける日本文化との関連性は、主に以下の二点に集約されます。

1. 自然との共生、「アニミズム」の精神

日本文化の根底には、自然界のあらゆるものに神や霊(たましい)が宿るというアニミズム的な思考があります。狸や狐(きつね)といった動物は、単なる獣ではなく、人知を超えた力を持つ「化け物」、あるいは「神使(しんし)」として認識されてきました。

この物語において、狸は人間を困らせる悪役であると同時に、ユーモラスな「芸能者」でもあります。和尚さんが狸を怖がらず、彼らの「腹鼓」という遊びを受け入れたことは、自然の力を排除するのではなく、その力を「場の活気」や「楽しみ」として受け入れ、共存の道を選んだことを意味します。これは、日本の農耕文化において、自然の恵みと災害の両方を受け入れながら生きてきた、日本人の自然観そのものです。恐れるべき存在も、敬意をもって接することで、調和の対象になり得るという思想がここに見て取れます。

2. 「和(わ)」を重んじる社会規範と柔軟性

この昔話が示す最も重要な教訓は、「和をもって貴しとなす」という、日本の根幹をなす精神です。

和尚さんは、腹鼓合戦という形で狸と「戦い」ましたが、それは相手を滅ぼすための戦いではなく、「相手の土俵に乗り、ルールの中で最高のパフォーマンスを見せる」という、一種の儀式的な競争でした。そして、最終的に勝敗を超えたところで、怪我をした相手を助けるという「慈悲」の行動によって、真の「和」が達成されます。

日本の社会では、直接的な対立や衝突を避け、まず相手を受け入れる「柔軟性」が重視されます。和尚さんが見せた、ユーモアと寛容さをもって異質なものに接し、最終的に「仲良しになる」という結末は、多様な集団が共存する日本社会において、対立を乗り越え、調和(ハーモニー)を生み出すための理想的なプロセスを描写していると言えるでしょう。

この物語は、海外の読者にとって、「日本人にとっての強さとは、支配ではなく、受容と慈悲から生まれる」という、深遠な文化の側面を理解する鍵となるはずです。

④読者に問いかける形で終了

さて、この「しょじょ寺の狸林」の物語を読まれたあなたは、どのように感じたでしょうか。

もしあなたが最初に寺にやってきた和尚さん、あるいは豪傑和尚だったとしたら、狸たちを追い出すために、どのような行動を取ったでしょうか?もしかすると、現代の私たちであれば、科学的な方法や、もっと実利的な手段を講じるかもしれません。

しかし、この風変わりな和尚さんが選んだのは、「相手の遊びに乗っかる」という、最もユーモラスで、最もリスクの高い方法でした。彼は、相手の意図を理解し、その行動を否定するのではなく、自らも「腹鼓」という非日常的な行為に参加することで、対立の構造を破壊し、信頼関係を築き上げました。

あなたにとっての「異質な存在」とは何ですか? それは、文化の違いかもしれませんし、価値観の相違かもしれません。

あなたなら、その異質なものや、困難な状況に対して、「怖れや力で排除する」道を選びますか?それとも、この和尚さんのように、「好奇心と寛容さをもって、共に楽しめる道」を探しますか?

この物語が、あなたの日常における人間関係や、文化的な違いへの向き合い方について、深く考えるきっかけとなれば幸いです。

⑤外部リンクとカテゴリー

【カテゴリー】

Japanese Folktale Series

【外部リンク】

- 證誠寺(しょうじょうじ)公式サイト:

この昔話の舞台となった、千葉県木更津市にあるお寺です。伝説の背景にある歴史を感じてください。

https://shojoji.net/ - 童謡「証城寺の狸囃子」 (Wikipedia):

この昔話からインスピレーションを得て作られた、日本で非常に有名な童謡についての解説です。

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%A8%BC%E5%9F%8E%E5%AF%BA%E3%81%AE%E7%8B%B8%E5%9B%83%E5%AD%90

コメント