Today, October 25th, commemorates the day the Shimabara Rebellion (島原の乱, *Shimabara no Ran*) broke out in 1637. This event, which shook the foundations of the early Tokugawa Shogunate, is one of the most significant and tragic episodes in Japanese history, profoundly impacting the nation’s political, social, and cultural trajectory for the next two centuries.

1. The Shimabara Rebellion: A Deep Dive into History, Culture, and Tragedy

The Shimabara Rebellion was a large-scale peasant uprising that occurred in the Shimabara Peninsula (modern-day Nagasaki Prefecture) and the Amakusa Islands (modern-day Kumamoto Prefecture) in Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s main islands. It was not a simple regional disturbance but a complex event driven by a convergence of severe factors:

Political Oppression and Economic Hardship

The primary catalyst was the brutal misrule and exorbitant tax collection by the local feudal lords, notably Matsukura Katsuie of the Shimabara Domain. During a period of poor harvests and famine, peasants were forced to pay taxes that far exceeded their land’s actual yield. Records even speak of horrific tortures used against those who could not pay, such as the infamous “Mino Odori” (Straw Raincoat Dance), where villagers were wrapped in straw mats and set on fire and mocked.

Religious Persecution

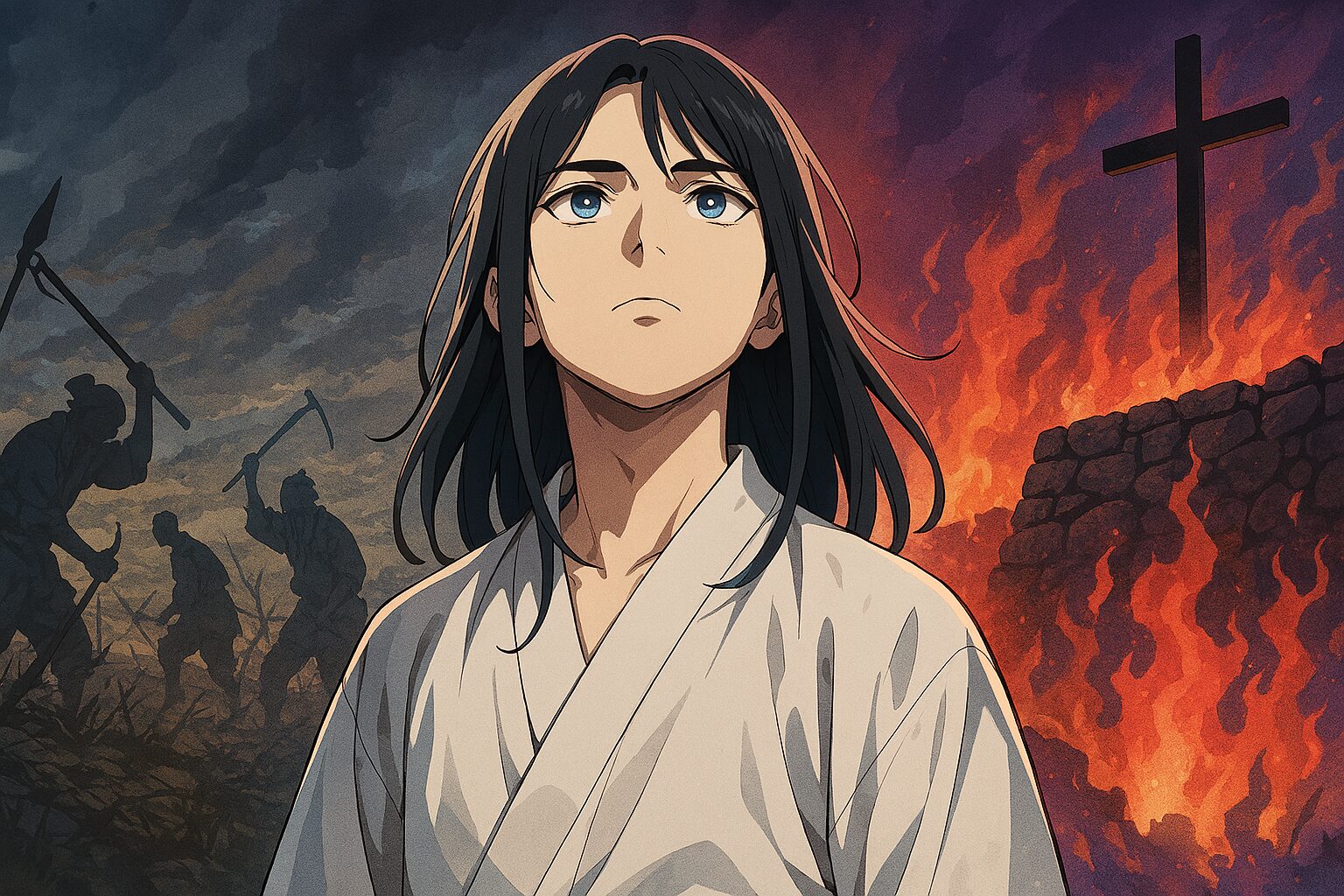

The region was a stronghold of Christianity, which had flourished after its introduction in the mid-16th century. The Tokugawa Shogunate viewed Christianity as a threat to its authority and national stability, leading to increasingly severe anti-Christian edicts and brutal suppression. Many of the peasants were Hidden Christians (*Kakure Kirishitan*), and the rebellion became heavily tinged with religious fervor. They fought not just for economic relief, but for their faith.

The Rise of a Young Messiah

The desperate and oppressed peasants and *rōnin* (masterless samurai) rallied around a charismatic teenage boy, Amakusa Shirō Tokisada (天草四郎). Shirō, only 16 at the time, was proclaimed a divine messenger and the *Fourth Son of Heaven* by the rebels, who saw him as the prophesied savior of the oppressed Christians. His mystical aura and purported miracles galvanized the masses.

The revolt began with the assassination of a local magistrate and rapidly spread, culminating in the estimated 37,000 rebels—comprising peasants, women, children, and *rōnin*—taking refuge in the ruins of the old **Hara Castle (原城)** on the Shimabara Peninsula.

The Shogunate dispatched a massive army of over 120,000 men, a coalition of forces from various western domains, to quell the uprising. This led to a desperate, three-month-long siege of Hara Castle. Despite fierce resistance, the rebels, weakened by starvation and lack of supplies, were ultimately overwhelmed in a final, bloody assault in the spring of 1638. Almost all the defenders, including Amakusa Shirō, were massacred or executed.

2. Reading the Rebellion: Its Connection to Japanese Culture and National Identity

The Shimabara Rebellion, though a military failure for the rebels, was a colossal event whose repercussions reshaped Japan’s national character and its place in the world.

The Reinforcement of *Sakoku* (鎖国, National Seclusion)

The most direct and profound consequence of the rebellion was the decisive acceleration of Japan’s isolationist policy. The Shogunate saw the involvement of foreign powers in Christian doctrine and the potential for a large-scale civil war as the ultimate danger. Shortly after the rebellion, in 1639, the Shogunate issued the final *Sakoku* Edict, completely banning Portuguese ships and solidifying a system where only the Dutch and the Chinese were allowed limited trade via Dejima in Nagasaki. For over 200 years, this policy effectively “froze” Japan’s contact with the outside world, fostering a uniquely isolated development of Japanese culture.

The Cultural Impact of Hidden Christianity

The complete suppression of the rebellion did not eradicate Christianity; it simply drove it deep underground. The Hidden Christians (*Kakure Kirishitan*) of the Shimabara and Nagasaki regions went to extraordinary lengths to preserve their faith, blending Christian prayers and customs with Buddhist and Shinto practices to evade detection. This resulted in a unique syncretic culture, with hidden relics, secret prayers passed down orally, and subtle Christian symbols woven into daily life. This resilience and commitment to personal faith, even under mortal threat, is a powerful, though often overlooked, element of the Japanese spiritual landscape.

The Shadow of Oppression and the Call for Justice

The rebellion serves as a stark historical reminder of the danger of unchecked political power and extreme injustice. While the Shogunate ultimately crushed the revolt, the sheer scale and intensity of the uprising demonstrated the breaking point of the common people. The fact that the Shimabara lord, Matsukura Katsuie, was later beheaded by the Shogunate—an exceedingly rare punishment for a feudal lord—showed that even the central government recognized the lord’s tyranny as the primary cause. This highlights an underlying, if repressed, cultural value in Japan for the necessity of good governance and accountability, even within a rigid feudal system.

The “Day of the Shimabara Rebellion” is therefore not merely a date of battle; it is the day that sealed Japan’s long isolation and simultaneously crystallized the powerful, enduring spirit of the people against insurmountable odds. It is the story of faith, oppression, and the ultimate sacrifice for freedom.

3. A Question for Our Readers

The courage and desperation of the people at Hara Castle led to a system of isolation that, while stifling, also allowed a truly unique Japanese culture to flourish for two centuries. If you were a citizen of Japan during this time, knowing that the rebellion would likely be crushed, would you have joined the uprising in a final, defiant act for freedom and faith, or would you have chosen to endure the oppression, focusing on secretly preserving your beliefs for the future? How much personal sacrifice is justified for a cause you know is doomed to fail?

4. Related Information

External Link (UNESCO World Heritage Site)

- Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region – UNESCO World Heritage Centre (The site includes Hara Castle and related locations.)

Internal Link (Related Category on this Blog)

10月25日:島原の乱の日 – 鎖国を決めた日本の悲劇と隠された信仰の文化

今日、10月25日は、1637年に島原の乱(島原の乱、*Shimabara no Ran*)が勃発した日です。この出来事は、初期の徳川幕府の基盤を揺るがし、その後の200年以上にわたり日本の政治、社会、文化の軌道を決定づける、最も重要かつ悲劇的なエピソードの一つです。

1. 島原の乱:歴史、文化、そして悲劇の深層

島原の乱は、九州の主要な島の一つである島原半島(現在の長崎県)と天草諸島(現在の熊本県)で起こった大規模な農民一揆です。これは単なる地域的な騒動ではなく、複数の深刻な要因が絡み合った複雑な事件でした。

政治的圧政と経済的困窮

最大の引き金は、地元の封建領主、特に島原藩主・松倉勝家による残忍な圧政と法外な年貢の取り立てでした。凶作と飢饉の時期にもかかわらず、農民は実際の石高をはるかに超える税を納めるよう強いられました。年貢を納められない者に対しては、筆舌に尽くしがたい拷問が行われ、その中には、村人を藁蓑(わらみの)で包んで火をつけ、苦しむ姿を「蓑踊り」と呼ぶ非道な行為の記録さえ残っています。

宗教的迫害

この地域は、16世紀半ばに伝来して以来、キリスト教の信仰が盛んな地でした。徳川幕府はキリスト教を自らの権威と国家の安定に対する脅威と見なし、キリシタン禁制の法令を強化し、弾圧は一層過酷になっていました。農民の多くは隠れキリシタン(*Kakure Kirishitan*)であり、一揆は経済的な救済だけでなく、信仰のための戦いという側面を強く持ちました。

若き救世主の出現

絶望と抑圧の淵にあった農民や浪人(主君を持たない侍)は、カリスマ的な少年、天草四郎時貞(あまくさしろうときさだ)のもとに結集しました。当時わずか16歳だった四郎は、反乱軍によって神の使者、そして抑圧されたキリシタンの預言された救世主として擁立されました。彼の神秘的なオーラと伝えられる奇跡は、大衆を熱狂させました。

反乱は代官殺害から始まり、急速に広がり、最終的に推定3万7千人の一揆軍—農民、女性、子供、そして浪人—が島原半島の先端にある廃城、原城(はらじょう)に立て籠もりました。

幕府は、この鎮圧のために12万を超える大軍を派遣し、原城を三ヶ月にわたって包囲しました。激しい抵抗にもかかわらず、飢餓と物資の欠乏で弱った一揆軍は、翌1638年の春の総攻撃でついに圧倒されました。天草四郎を含む立て籠もり者たちは、ほぼ全員が虐殺されるか処刑されました。

2. 乱から読み解く:日本文化と国民性への関連

島原の乱は、反乱軍にとっては軍事的な敗北でしたが、その余波は日本の国民性を形作り、世界における日本の立ち位置を決定づける巨大な出来事となりました。

鎖国(*Sakoku*)体制の強化

乱の最も直接的かつ深遠な結果は、日本の孤立主義政策、すなわち鎖国(さこく)の決定的な加速でした。幕府は、キリスト教の教義を通じた外国勢力の関与と、それに伴う大規模な内戦の可能性を最大の危険と見なしました。乱の直後、1639年にポルトガル船の入港を全面的に禁止する最終的な鎖国令が発布され、日本は長崎の出島を介したオランダと中国との限定的な貿易を除き、外界との接触を事実上断ち切りました。この政策は200年以上にわたり、「独自の」日本文化を育む孤立した発展を促すことになりました。

隠された信仰の文化

一揆の完全な鎮圧は、キリスト教を根絶したわけではなく、ただ地下深くへと追いやっただけでした。島原と長崎地域の隠れキリシタン(*Kakure Kirishitan*)たちは、発覚を避けるために、キリスト教の祈りや習慣を仏教や神道の慣習と融合させ、驚くべき努力で信仰を保ちました。これにより、密かに受け継がれた秘密の祈り、日常生活に織り込まれた微妙なキリスト教のシンボルなど、独自のシンクレティズム(混交宗教)文化が生まれました。この、命の危険に晒されながらも個人的な信仰を貫き通した強靭さは、日本の精神的景観において、しばしば見過ごされがちな、しかし力強い要素です。

圧政の影と正義への問い

この乱は、権力の監視の欠如と極度の不正義がもたらす危険を痛烈に示しています。幕府は最終的に反乱を鎮圧しましたが、その規模と激しさは、庶民の我慢の限界を示しました。島原藩主・松倉勝家が後に改易(領地の没収)の上、斬首刑に処されたという事実は—大名としては極めて異例の罰則—、中央政府でさえ、領主の暴政がこの悲劇の主要な原因であったことを認識していたことを示しています。これは、厳格な封建制度の中にあっても、善政と説明責任の必要性という、日本文化の根底にある価値観を浮き彫りにしています。

「島原の乱の日」は、単なる戦闘の日付ではありません。それは、日本の長い孤立を決定づけた日であり、同時に、乗り越えられない壁に立ち向かった人々の、強靭で不屈の精神を具現化した日でもあります。信仰、抑圧、そして自由のための究極の犠牲の物語なのです。

3. 読者の皆様へ問いかけ

原城の人々の勇気と絶望は、その後200年以上にわたり、真に独自の日本文化を育む孤立した体制をもたらしました。もしあなたがこの時代に生きていたとして、一揆が鎮圧される可能性が高いと知りながら、自由と信仰のための最後の抵抗として蜂起に参加しましたか?それとも、圧政に耐え忍び、信仰を秘密裏に未来へ継承することに焦点を当てましたか?失敗が確実な大義のために、どこまで個人の犠牲は正当化されるのでしょうか?

4. 関連情報

外部リンク(ユネスコ世界遺産)

- Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region – UNESCO World Heritage Centre(原城跡を含む、関連する場所が紹介されています。)

コメント