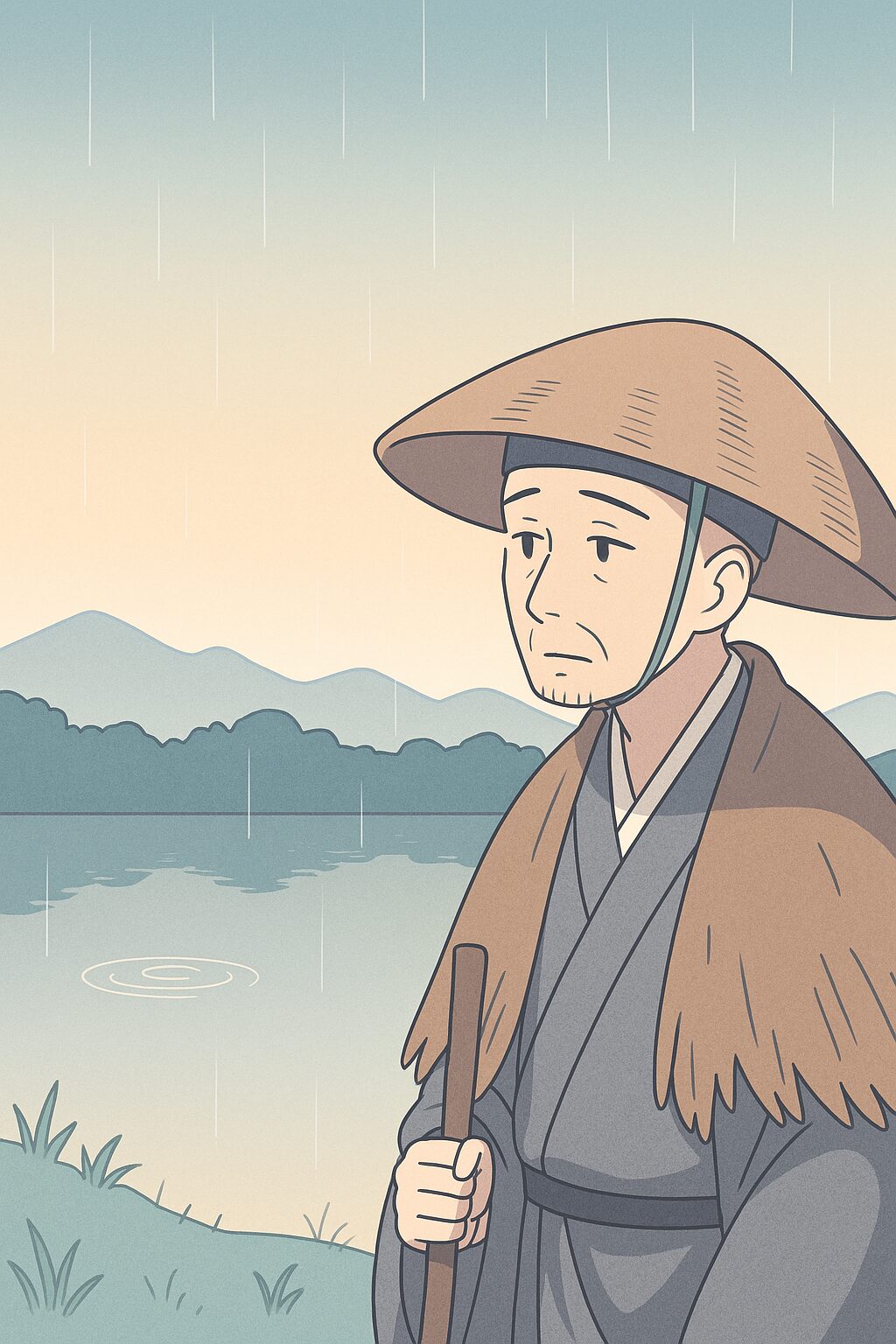

October 12th on the modern solar calendar (which often corresponds to the traditional date for this memorial) marks an incredibly significant day in Japanese literary and cultural history: Bashō-ki (芭蕉忌). This is the memorial day for Matsuo Bashō (松尾芭蕉, 1644–1694), the universally acclaimed master and “Poetic Saint” (*Haisei*) of *Haikai*, the form that evolved into modern Haiku. Today, we delve into the life of this great itinerant poet and the profound cultural legacy he left behind.

- ① What is Bashō-ki? History, Culture, and the Poetics of “Shigure”

- ② Decoding the Culture: The Japanese Spirit of Pilgrimage and the Art of “Empty Space”

- ③ A Question to Our Global Readers

- ④ Useful Links for Further Reading

- ① 芭蕉忌とは? 歴史、文化、そして「時雨」の情景

- ② 芭蕉忌から読み解く日本の心:旅の思想と「余白」の文化

- ③ 読者への問いかけ:現代の「奥の細道」

- ④ 参考リンク

① What is Bashō-ki? History, Culture, and the Poetics of “Shigure”

Bashō-ki commemorates the death of Bashō, who passed away in Osaka while on a journey. The day is also known by the deeply poetic name Shigure-ki (時雨忌). *Shigure* refers to the intermittent, passing rain of late autumn or early winter. This seasonal word (*kigo*) was a favorite of Bashō, symbolizing the fleeting beauty, quiet austerity, and subtle melancholy found in nature. The day is also respectfully called *Ōkina-ki* (翁忌, Old Man’s Day) and *Tōsei-ki* (桃青忌, after an earlier pen name).

Bashō’s paramount achievement was elevating *Haikai*—a popular, often lighthearted, collaborative verse form—into a high literary art, a profound philosophical pursuit known as **Shōfū (蕉風)**, or the Bashō style. His poetry is an embodiment of quintessential Japanese aesthetic principles:

Bashō’s Aesthetics: The Art of the Ephemeral

- Wabi-Sabi (侘び寂び): The appreciation of beauty that is imperfect, impermanent, and modest. His most famous poem, “古池や 蛙飛びこむ 水の音” (*Furu ike ya / kawazu tobikomu / mizu no oto* – “Old pond… / a frog leaps in / water sound”), captures this perfectly, focusing on a small moment that emphasizes the surrounding stillness.

- Shiori (しをり): A sense of delicate grace and emotional depth, evoking deep empathy for the subject.

- Hosomi (細み): A keen, minute sensitivity to the object being described, allowing the poet to achieve unity with the subject (*butsuga ichinyo*).

- Karumi (軽み): His final style, which emphasizes lightness, naturalness, and apparent simplicity, conveying profound truths with an unlabored, sincere air.

His masterpiece, **”Oku no Hosomichi” (おくのほそ道, *The Narrow Road to the Deep North*)**, is a poetic travelogue that narrates his 2,400-kilometer, 150-day spiritual and physical journey across northern Japan. It is the ultimate expression of the “wandering poet” (*hyōhaku no shijin*) spirit, fusing historical weight, natural observation, and immediate personal experience.

Today, on Bashō-ki, commemorative ceremonies known as **Bashō-sai (芭蕉祭)** are held, particularly in his birthplace of Iga (Mie Prefecture) and at the Gichū-ji Temple in Ōtsu (Shiga Prefecture), where he is interred. These events typically involve poetry readings and lectures, ensuring his enduring legacy.

② Decoding the Culture: The Japanese Spirit of Pilgrimage and the Art of “Empty Space”

The annual observance of Bashō-ki provides a powerful cultural moment to reflect on the Japanese “philosophy of the journey” and the “culture of empty space.” Bashō’s constant traveling was more than a hobby; it was a spiritual discipline to attain **Muga (無我)**, or selflessness. By continually shedding the comfort of his home, he sought to observe the world without the clouding of ego. This dedication to an itinerant, austere life echoes the Zen Buddhist principles that underpin much of Japanese aesthetic thought—that true understanding is often found in transience and simplicity.

Haiku: The World in Seventeen Syllables

Haiku, the form distilled from Bashō’s work, is the ultimate expression of Japanese conciseness. The five-seven-five syllable structure, combined with a single *kigo* (seasonal word), demands an act of cultural discipline: **Intense Focus and Condensation**.

Haiku masters deliberately omit extraneous details, leaving significant **Yohaku (余白)**, or “empty space.” This empty space is crucial; it compels the reader to engage their imagination, filling in the context and deepening the emotional resonance. When Bashō writes, “夏草や 兵どもが 夢の跡” (*Natsu kusa ya / tsuwamono-domo ga / yume no ato* – “Summer grass… / the vestiges of dreams / of mighty warriors”), he is not just describing grass. He is *feeling* the vast, silent history of the place through the growth of nature. Haiku is, therefore, a testament to the Japanese capacity for finding universal truths and deep emotion in a single, fleeting detail.

Commemorating Bashō is a recommitment to this cultural mission: to pause, to look closely, and to sense the profound, quiet beauty within the everyday.

③ A Question to Our Global Readers

As we commemorate Bashō, the poet who chose the path of the wandering ascetic over status and comfort, we are compelled to examine our own relationship with the world. In our era of endless digital chatter and relentless activity, what is the “narrow road” that we must travel to find our own sense of **Karumi** (lightness and sincerity)?

How can we, in our modern, fast-paced lives, truly pause and listen for the stillness of the “water sound” in the midst of our own “old pond”?

Would you consider embarking on a journey—be it physical or introspective—to strip away the superficial and discover the *hosomi* (delicate sensitivity) of your own life? Or do you believe that contemporary life itself offers enough material for profound, concise observation? What would your five-seven-five Haiku about your day be?

④ Useful Links for Further Reading

- Matsuo Bashō – Wikipedia (English): Comprehensive information on his life, major works, and historical impact. Matsuo Bashō – Wikipedia

- Internal Link: Explore More Japanese Culture and Commemorative Days — What’s Today’s Special Day Series

10月12日:芭蕉忌 – 日本の詩魂を偲ぶ旅人の日

現代の太陽暦で10月12日(旧暦では通常11月頃)は、日本の文学史、文化史において極めて重要な日、芭蕉忌(ばしょうき)です。これは、「俳聖」とも称される、世界にその名を知られる俳諧の大家、松尾芭蕉(まつお・ばしょう、1644–1694年)の命日を記念する日です。本日は、この偉大な漂泊の詩人の生涯と、彼が日本の心に残した深い足跡を辿ります。

① 芭蕉忌とは? 歴史、文化、そして「時雨」の情景

芭蕉忌は、旅先の大阪で客死した芭蕉を偲ぶ日です。この日は、その別名時雨忌(しぐれき)としても知られています。時雨とは、晩秋から初冬にかけて、降ったり止んだりする通り雨のこと。この季語は、芭蕉が特に愛し、そのはかない美しさや静かな寂しさを表現するのに多用しました。他にも、晩年の俳号にちなむ桃青忌(とうせいき)や、門人たちが敬意を込めて呼んだ翁忌(おきなき)という呼び名もあります。

松尾芭蕉の最大の功績は、それまで庶民の娯楽や言葉遊びの域を出なかった俳諧(連歌から派生した五・七・五の句)を、哲学的・芸術的な高みへと引き上げたことにあります。彼が確立したスタイルは蕉風(しょうふう)と呼ばれ、日本文化特有の美意識を色濃く反映しています。

芭蕉の俳句美学:Wabi-Sabiを超えて

- 侘び寂び(わびさび): 簡素で静かなものの中に、奥深い美しさや時間の経過を見出す精神。彼の代表句「古池や 蛙飛びこむ 水の音」は、静寂を一瞬の音で破ることで、この美学を完璧に表現しています。

- しをり(しおり): 句の背後に漂う、優美で繊細な情感、対象への共感や哀れみの情。

- 細み(ほそみ): 事物の本質を微細な感覚で捉え、客観的に描写しようとする感性。

- 軽み(かるみ): 晩年の境地。平明でさりげない表現の中に、奥深い真実や詩情を宿らせることを目指しました。

彼の紀行文学の金字塔『おくのほそ道』は、約150日間にわたる約2,400kmの旅の記録であり、単なる旅行記ではなく、歴史と自然、そして人間の営みを五・七・五に昇華させた文学作品です。芭蕉は生涯を通じて旅を続け、その旅路こそが彼の俳句の源泉でした。

命日である今日、彼の生まれた三重県伊賀市や、遺言により葬られた滋賀県大津市の義仲寺(ぎちゅうじ)など、各地で芭蕉祭(ばしょうさい)が行われ、献句や講演会を通じてその偉業が偲ばれます。

② 芭蕉忌から読み解く日本の心:旅の思想と「余白」の文化

芭蕉忌が毎年巡ってくることは、日本人にとって、彼の遺した「旅の思想」と「余白の文化」を見つめ直す機会となります。芭蕉の旅は、単なる移動ではなく、**無我(むが)**の境地を求める修行でした。彼は、定住を離れ、あえて不便な旅路を選ぶことで、エゴや俗世のしがらみを削ぎ落とし、世界を純粋に観察しようとしました。この求道的な姿勢は、仏教や禅の精神が深く根付いた日本文化の精神性を象徴しています。

俳句:世界の縮図としての十七音

わずか十七音(五・七・五)という極端な短詩形に、必ず季語(季節を表す言葉)を一つ組み込むという俳句のルールは、日本文化における**集中と凝縮**の美学を体現しています。

俳句は、余計な説明を省き、**余白(よはく)**を多く残します。この余白こそが、読み手に無限の想像力を喚起させ、詩情を深めるのです。芭蕉が詠んだ「夏草や 兵どもが 夢の跡」という句は、目の前の夏草という小さな事象から、遠い昔の武士たちの盛衰という壮大な歴史の流れ、人生の無常を読み取ります。

この十七音への徹底的なこだわりは、細部に神が宿るという日本の伝統的な職人精神にも通じています。短い詩の中に、時代や場所を超越した普遍的な感情を込めること。それが、芭蕉が俳諧を文学へと昇華させた偉大な功績であり、私たちが芭蕉忌を通して受け継ぐべき日本の心なのです。

③ 読者への問いかけ:現代の「奥の細道」

絶え間ない情報、目まぐるしく変化する技術、そしてデジタルな繋がりが支配する現代社会において、私たちはどれほど「立ち止まり、観察する」という行為を忘れてしまっているでしょうか。

地位や富を捨てて旅に出た芭蕉の生き方から、私たちは何を学ぶことができるでしょうか。私たちの日常における「古池」はどこにあり、どんな「水の音」が聞こえているでしょうか。

あなたにとっての現代の「奥の細道」とは何でしょうか。多忙な日々の中で、あなたはどのようにして**細み(繊細な感受性)**を保ち、人生の**軽み(軽やかで真摯な姿勢)**を見出そうとしますか。この記事を読んだ今、あなた自身の「今日」を五・七・五で表現するとしたら、どんな句になりますか?

④ 参考リンク

- 松尾芭蕉 – Wikipedia (日本語): 芭蕉の生涯、代表作、俳諧への影響について詳細な情報があります。 松尾芭蕉 – Wikipedia

- 当ブログ内リンク: 日本の文学と禅の繋がりを探る — 和の心と記念日シリーズ

コメント