The Folktale Story: Nezumi no Sumo (The Mice’s Sumo)

Once upon a time, in a poor mountain village, lived a kind-hearted old man and woman. They led a humble life, but their spirits were always rich.

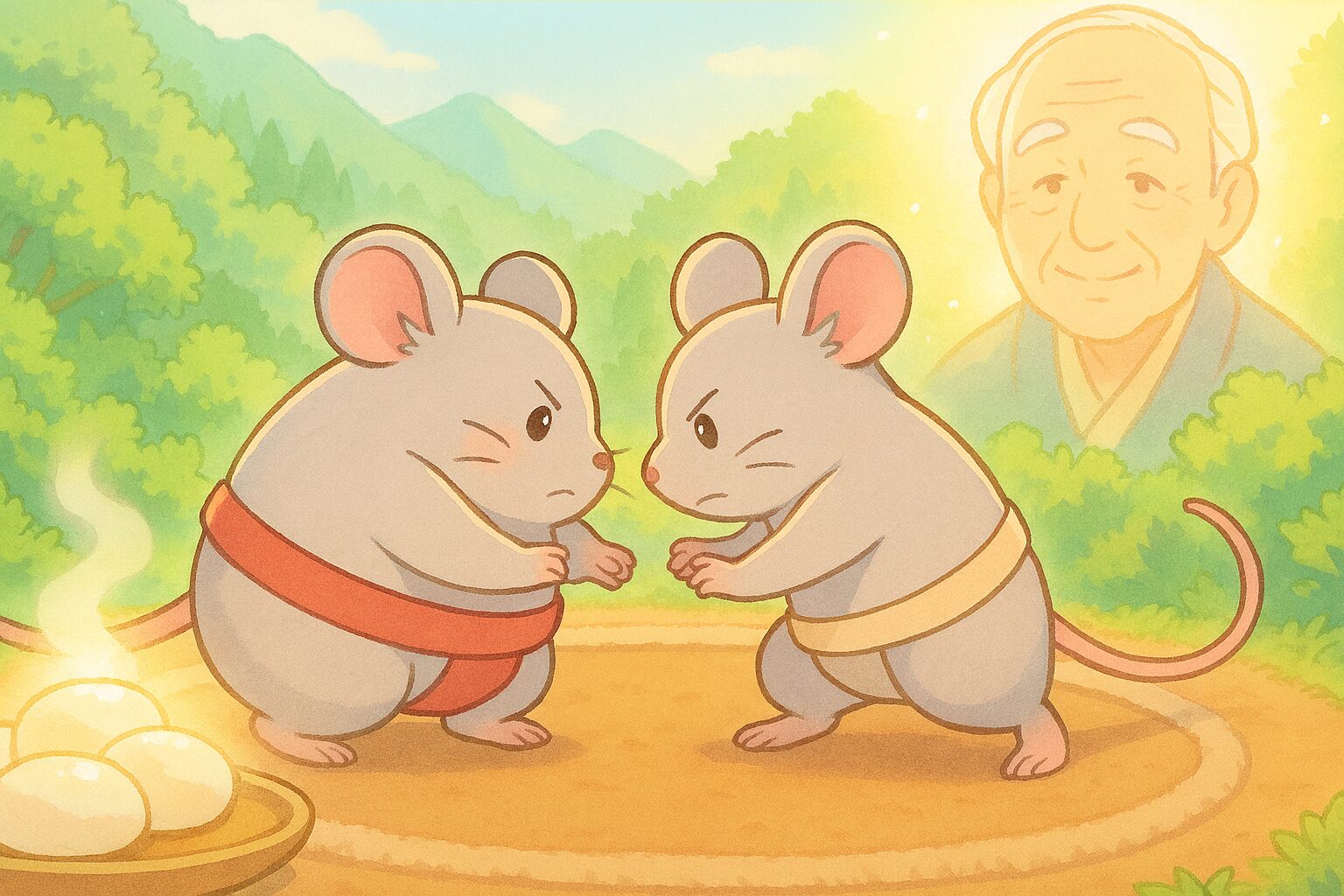

One day, as the old man went to the mountain to gather firewood, he heard a spirited cheer of “Denkasho, Denkasho” coming from somewhere. When he quietly approached the thicket where the sound came from, he found two mice wrestling in a sumo match!

One mouse was skinny and looked frail. The other was noticeably plump and seemed strong. The skinny mouse was the one living in the old man’s humble house. The plump one belonged to the richest man in the village, the “Chōja” (wealthy man).

The match was clearly one-sided. The plump mouse from the Chōja’s house kept shouting “Dosukoi!” and throwing the skinny mouse out of the ring. No matter how many times the skinny mouse stood up, he was immediately tossed out. The old man felt a pang of sadness: “Oh, the poor thing. Our mouse is always losing, he must be so frustrated.”

Returning home, the old man told his wife about the mice’s sumo. The old woman also sympathized: “That’s a pity. Always losing will certainly dampen a mouse’s spirit.”

Together, they came up with an idea.

“Ah, we still have some rice set aside for the New Year’s mochi (rice cake). Let’s make some mochi and feed it to the mouse. I’m sure it will gain strength and finally be able to win!”

That night, the old man and woman lovingly pounded the rice into mochi. They rolled the freshly made mochi into balls and secretly placed them on the mice’s path. They cheered in their hearts: “Now, eat plenty and do your best tomorrow!”

The next day, when the old man went back to the mountain, he heard “Denkasho, Denkasho” again. When he drew closer, he saw a miracle: the skinny mouse was now throwing the plump mouse out of the ring!

“He did it! Our mouse won!” the old man rejoiced.

The Chōja’s mouse, who had been losing consistently, was astonished and asked the skinny mouse:

“How did you get so strong all of a sudden? Did you eat something special?”

The skinny mouse proudly replied:

“Yes, actually! My Grandpa and Grandma made me mochi and let me eat it. That mochi gave me all this power!”

Upon hearing this, the Chōja’s mouse was extremely envious. While the Chōja’s house had more rice than they could ever eat, no one there would ever make mochi for a mouse.

“Please! Can you let me eat that mochi too? I want to be strong!”

The skinny mouse was troubled, but knowing the kindness of the old man and woman, he assumed they would share and invited the Chōja’s mouse.

That night, the Chōja’s mouse, as a token of thanks, secretly brought a bag full of Koban (gold coins) from the Chōja’s storehouse to the old man’s house.

The old man and woman understood that the mice were simply pure-hearted and wanted to gain strength for their beloved sumo. They happily made plenty of mochi for both of them, and even sewed two small, red mawashi (sumo belts).

The two mice ate the mochi to their hearts’ content, tied on their red mawashi, and immediately started wrestling in front of the old man. The old man acted as the “Gyōji” (referee), shouting “Hakkek-yoi, Nokotta!” The mice exerted all their strength, praising each other’s efforts.

And so, thanks to the gold coins brought by the mouse, the kind-hearted old man and woman were freed from poverty and lived happily ever after. And the two mice continued to enjoy their sumo wrestling in friendship.

Examining the Folktale: The Nature of Strength and Heart

“The Mice’s Sumo” is not just a charming animal story. The key points to examine in this narrative are the **relationship between strength, wealth, and kindness.**

First, let’s look at the contrast between the two households and the mice living there:

- The Poor Old Man’s House: **Poor but rich in spirit**. They show deep compassion and love for the mouse, offering the precious mochi for its wish without hesitation. The mouse of this house gains “love” and “nourishment” and unlocks its true strength.

- The Chōja’s House: **Wealthy but cold in spirit**. Although the house is overflowing with rice, the mouse laments that no one will give him mochi. This mouse lives in physical wealth but starves for “spiritual nourishment.”

This story conveys a powerful message: **”True strength is not born from physical wealth or stature, but from support and love received from the heart.”** The skinny mouse became strong not only because of the nutritious mochi but also because of the psychological boost of knowing he had someone who believed in and cheered for him.

The Chōja’s mouse bringing the gold coins is also significant. Despite living in a rich house, he has a pure desire to become stronger and understands the **courtesy (Reigi)** of not coming empty-handed when receiving a favor. This suggests the Japanese spirit of **Giri (duty) and Ongaeshi (returning a favor)**, regardless of the amount of wealth. As a result, the old man and woman receive wealth as an “Ongaeshi” for their unconditional love and kindness toward the mice.

Unlocking Japanese Culture: Sumo, Daikokuten, and the Spirit of “Osuwake”

1. Sumo: The National Sport and Its Spirituality

The setting of mice performing sumo suggests that for the Japanese, Sumo is more than a mere sport; it is a **Shinto ritual (Shinji)**. Historically, Sumo was performed as a sacred ceremony to pray for or predict a good harvest. By wrestling, the mice transform the location into a kind of **sacred “Dohyō” (Sumo ring)**, adding a pure atmosphere to the story. It expresses the spirit of overcoming physical differences through effort and showing respect to both the winner and the loser.

2. The Mice and the Faith in “Daikokuten”

The conclusion, where the mice bring wealth to the old couple, is strongly linked to ancient Japanese beliefs. The mouse is considered a messenger of **Daikokuten (Daikoku-sama)**, one of the Seven Gods of Fortune. Daikokuten is the god of good harvest and wealth.

Since mice eat rice, the symbol of wealth, they have been viewed in Japan with a dual nature: a pest, yet also a **”bringer of fortune.”** The mice bringing the gold coins can be interpreted as a **reward from Daikoku-sama** for the old couple’s good deeds. This embodies the Japanese ethical value—also seen in other folktales like “Nezumi Jōdo” (The Mice’s Paradise)—that **”a kind heart will always be rewarded.”**

3. The Culture of “Mochi” and “Osuwake”

The “Mochi” at the core of this story is a special food for the Japanese. It is a sacred food eaten on *Hare no Hi* (special, festive occasions) like the New Year, symbolizing **vitality and abundance.**

The act of the old man and woman giving the mochi to the mice, even though it meant sacrificing their own precious food, perfectly encapsulates the Japanese spirit of **”Osuwake” (sharing)** and **”unconditional love.”** The virtue of the poor sharing with those even weaker or in need reflects the Japanese ideal of **”consideration for the vulnerable.”** It clearly teaches the lesson that pure kindness, given without expectation of return, ultimately brings the greatest reward.

A Question for Our Readers

“The Mice’s Sumo” poses an essential question for us living in modern society.

If you were to find a mouse losing a sumo match in the mountains, what would you do?

Could you show **kindness without expecting anything in return**, sharing something valuable you possess? Or, like the Chōja’s mouse, can you maintain a **pure heart and courtesy**, even when living in a privileged environment?

In an age that pursues wealth and success, this story reminds us that **”richness of the heart” is the true treasure.** The kindness that compels us to sympathize with the small efforts and struggles of others and take action is the key. It is what enriches our own world.

What resonated with you after reading this folktale? And today, to whom would you like to share a “mochi”? We look forward to hearing your thoughts.

External and Internal Links

- History and Culture of Sumo

Japan Sumo Association Official Website (English) - About Daikokuten and the Seven Gods of Fortune

Japanese Tourism Information Page (e.g., JNTO – Japan National Tourism Organization) - Mochi Culture

Page Introducing Japanese Food Culture (e.g., MAFF English Page)

Category Page:

Japanese Folktale Series

ねずみのすもう:優しさがもたらす奇跡と、日本の心

昔話のストーリー:ねずみのすもう

むかしむかし、ある貧しい山里に、心優しいおじいさんとおばあさんが住んでいました。二人は慎ましく暮らしていましたが、心はいつも豊かでした。

ある日、おじいさんが山へ柴刈りに出かけると、どこからか「でんかしょ、でんかしょ」という威勢の良いかけ声が聞こえてきました。声のする茂みにそっと近づいてみると、なんと二匹のねずみが相撲をとっているではありませんか。

一匹は痩せっぽちで、ひ弱そう。もう一匹は見るからに太って丸々としていて、力がありそうです。痩せているねずみは、おじいさんの家に住み着いているねずみでした。太っているねずみは、村一番の金持ちである長者の家に住むねずみでした。

勝負は一目瞭然。長者の家の太いねずみが、「どすこい!」とばかりに痩せねずみを投げ飛ばしてばかり。痩せねずみは何度立ち上がっても、すぐに土俵の外へ転がされてしまいます。「ああ、かわいそうに。うちのねずみは、いつも負けてばかりで、よほど悔しいだろうに」とおじいさんは心を痛めました。

家へ帰ったおじいさんは、おばあさんにねずみの相撲の話をしました。おばあさんも「それはかわいそうに。負けてばかりでは、ねずみだって元気がなくなるでしょう」と同情します。

そこで二人は、あることを思いつきました。

「そうじゃ、お正月用にと取っておいたもち米があるだろう。あれで餅をついて、ねずみに食べさせてやろう。きっと力がついて、勝てるようになるに違いない」

夜になり、おじいさんとおばあさんは心を込めて餅をつきました。つきたてのもちを丸めて、ねずみの通り道にそっと置いておきました。そして、「さあ、これでたっぷり食べて、明日は頑張るんだぞ」と心の中で応援しました。

翌日、おじいさんが再び山へ行くと、また「でんかしょ、でんかしょ」と声が聞こえます。近づいてみると、なんと今度は、昨日の痩せねずみが太いねずみを投げ飛ばしているではありませんか!

「やったぞ!うちのねずみが勝った!」とおじいさんは大喜びです。

負け続けていた長者のねずみは、驚いて痩せねずみに尋ねました。

「お前、どうして急にそんなに強くなったんだい?何か特別なものを食べたのかい?」

痩せねずみは得意げに答えました。

「うん、実はね、うちのおじいさんとおばあさんが、餅をついて食べさせてくれたんだ。あの餅のおかげで、こんなに力が出たんだよ」

それを聞いた長者のねずみは、羨ましくてたまりません。長者の家には食べきれないほどの米があるのに、誰もねずみのためになんて餅をついてくれません。

「お願いだ!僕にもその餅を食べさせてくれないか?僕も強くなりたいんだ!」

痩せねずみは困りましたが、優しいおじいさんとおばあさんのことですから、きっと分けてくれるだろうと思い、長者のねずみを誘いました。

その夜、長者のねずみは、お礼の印にと、長者の蔵からこっそりと小判の入った袋を背負って、おじいさんの家にやってきました。

おじいさんとおばあさんは、ねずみが相撲好きで、ただ純粋に力をつけたいだけなのだと察し、二匹のためにたっぷりの餅をついて、赤い小さなふんどしまで縫ってあげました。

二匹のねずみは、餅を心ゆくまで食べ、赤いふんどしを締めて、早速おじいさんの前で相撲を始めました。おじいさんは行司役となり、「はっけよい、のこった!」と声をかけます。ねずみたちは、どちらも力を出し切り、お互いを称え合いました。

こうして、心優しいおじいさんとおばあさんは、ねずみが運んできた小判のおかげで、貧しさから解放され、いつまでも幸せに暮らしました。そして、二匹のねずみは、その後も仲良く相撲を取り続けたということです。

昔話を考察する:力と心のあり方

「ねずみのすもう」は、単なるかわいらしい動物の物語ではありません。この物語の考察すべき点は、力と富、そして優しさの関係性です。

まず、対比される二つの家と、そこに住むねずみたちに注目しましょう。

- 貧しいおじいさんの家:貧しいが心は豊か。ねずみへの深い同情と愛情があり、ねずみの願いのために貴重な食料である餅を惜しみなく提供します。この家のねずみは、餅という「愛情」と「栄養」を得て、真の力を発揮します。

- 長者の家:裕福だが心は冷たい。長者の家には米が溢れているにもかかわらず、ねずみは「餅なんてくれない」と嘆きます。この家のねずみは、物理的な富の中で暮らしていながら、「心の栄養」に飢えています。

この物語は、「本当の力は、物理的な富や体格ではなく、心から得られる支援と愛情によって生まれる」という強いメッセージを伝えています。痩せねずみが強くなったのは、餅という栄養源もさることながら、「自分を応援してくれる人がいる」という心の支えがあったからです。

また、長者のねずみが小判を持ってきた行動も重要です。長者のねずみは、お金持ちの家に住んでいながら、単に強くなりたいという純粋な願いを持ち、恩恵を受けるにあたって「手ぶらではいけない」という礼儀を知っています。これは、富の多寡にかかわらず、日本人が大切にする義理と恩返しの精神を示唆しています。結果として、おじいさんとおばあさんは、ねずみへの無償の愛と優しさの「恩返し」として、富を得ることになるのです。

昔話から何を読み解き、日本文化との関連を紹介する

1. 国技「相撲」と精神性

ねずみが相撲をとるという設定は、日本人にとって相撲が単なる格闘技以上の、神事(神道の儀式)に近い文化であることを示しています。相撲は、古来より豊作を占う神聖な儀式として行われてきました。ねずみたちが相撲をとることで、その場所が一種の神聖な「土俵」となり、物語全体に清らかな雰囲気を加えています。相撲を通して、体格差を乗り越える努力と、勝者・敗者に対する敬意の精神を表現しているのです。

2. ねずみと「大黒様」の信仰

ねずみがおじいさんに富をもたらすという結末は、日本の古い信仰と強く結びついています。ねずみは、七福神の一人である大黒天(だいこくてん)の使いとされています。大黒天は五穀豊穣、財福の神です。

特に日本では、ねずみが富の象徴である米を食べることから、一見害獣でありながらも、同時に「富を運ぶ者」という二面性を持って信仰されてきました。この物語でねずみが小判を持ってきたのは、おじいさんとおばあさんの善行に対する大黒様からの報い、つまり「福」を運んできたと解釈できます。「ねずみ浄土」のような他の昔話にも見られる、「善良な心には必ず報いがある」という日本の倫理観を体現しています。

3. 「お餅」と「お裾分け」の文化

この物語の核となる「餅」は、日本人にとって特別な食べ物です。餅は、正月や祭りなどのハレの日(非日常的な晴れやかな日)に食べる神聖な食べ物であり、生命力と豊穣の象徴です。

おじいさんとおばあさんが、自分たちが食べる分を削ってまで餅をねずみに与える行為は、まさに日本の「お裾分け」(分け与える文化)と「無償の愛」の精神です。特に貧しい者が、さらに弱い者や困っている者に分け与えるという行動は、「弱者への配慮」を尊ぶ日本人の美徳を映し出しています。見返りを求めない純粋な優しさこそが、最終的に最高の恩恵をもたらすという教訓を明確に示しています。

読者への問いかけ

「ねずみのすもう」は、現代社会に生きる私たちにも大切な問いを投げかけます。

あなたは、もし山で相撲に負けているねずみを見つけたら、どうしますか?

自分の持っている大切なものを分け与えて、見返りを求めない優しさを示すことができるでしょうか。あるいは、長者のねずみのように、恵まれた環境にありながらも、純粋な心と礼儀を忘れずにいられるでしょうか。

富や成功を追い求める現代において、この物語は「心の豊かさ」こそが真の財産であることを教えてくれます。他者の小さな努力や苦しみに心を寄せ、行動に移す優しさ。それが、私たち自身の世界を豊かにする鍵となるのです。

この昔話を読んで、あなたの心に響いたことは何ですか?そして、今日、あなたは誰に、どのような「餅」を分け与えたいと思いますか?ぜひ、あなたの考えを聞かせてください。

外部リンク・内部リンク

- 相撲の歴史と文化

日本相撲協会公式サイト(英語ページ) - 大黒天と七福神について

日本の観光情報ページ(例:JNTO – 日本政府観光局) - 餅の文化

日本の食文化を紹介するページ(例:農林水産省の英語ページ)

カテゴリーページ:

Japanese Folktale Series

コメント