- 🌿 Introduction: A Time When the Spirits Come Home

- 🐴 What Are Shōryō-uma and Shōryō-ushi?

- 🔥 Welcoming and Sending Off: The Fires That Guide the Way

- 🏡 Where and How to Display Spirit Animals

- 🧂 What Happens After Obon?

- 🌸 The Heart of Obon: Connection Beyond Time

- 🧘♂️ Spirituality Beyond Religion

- ✨ Conclusion: Why Spirit Horses Still Matter

- 🌿はじめに:年に一度、ご先祖様が帰ってくる日

- 🐴精霊馬(しょうりょううま)と精霊牛(しょうりょううし)とは?

- 🔥迎え火と送り火:道しるべとしての炎

- 🏡飾る場所とタイミング:仏壇と盆棚

- 🧂処分方法:感謝と清めの心を込めて

- 🌸お盆の本質:命のつながりを感じる時間

- ✨まとめ:精霊馬に込められた「迎える心」

🌿 Introduction: A Time When the Spirits Come Home

Every summer in Japan, a quiet and sacred tradition unfolds: Obon. From August 13 to 16, families across the country prepare to welcome the spirits of their ancestors back home. They clean altars, visit graves, light guiding fires, and offer food—not out of obligation, but out of love and remembrance.

Obon is more than a religious ritual. It’s a moment to reconnect with the past, to honor those who came before, and to reflect on the invisible threads that bind generations together.

🐴 What Are Shōryō-uma and Shōryō-ushi?

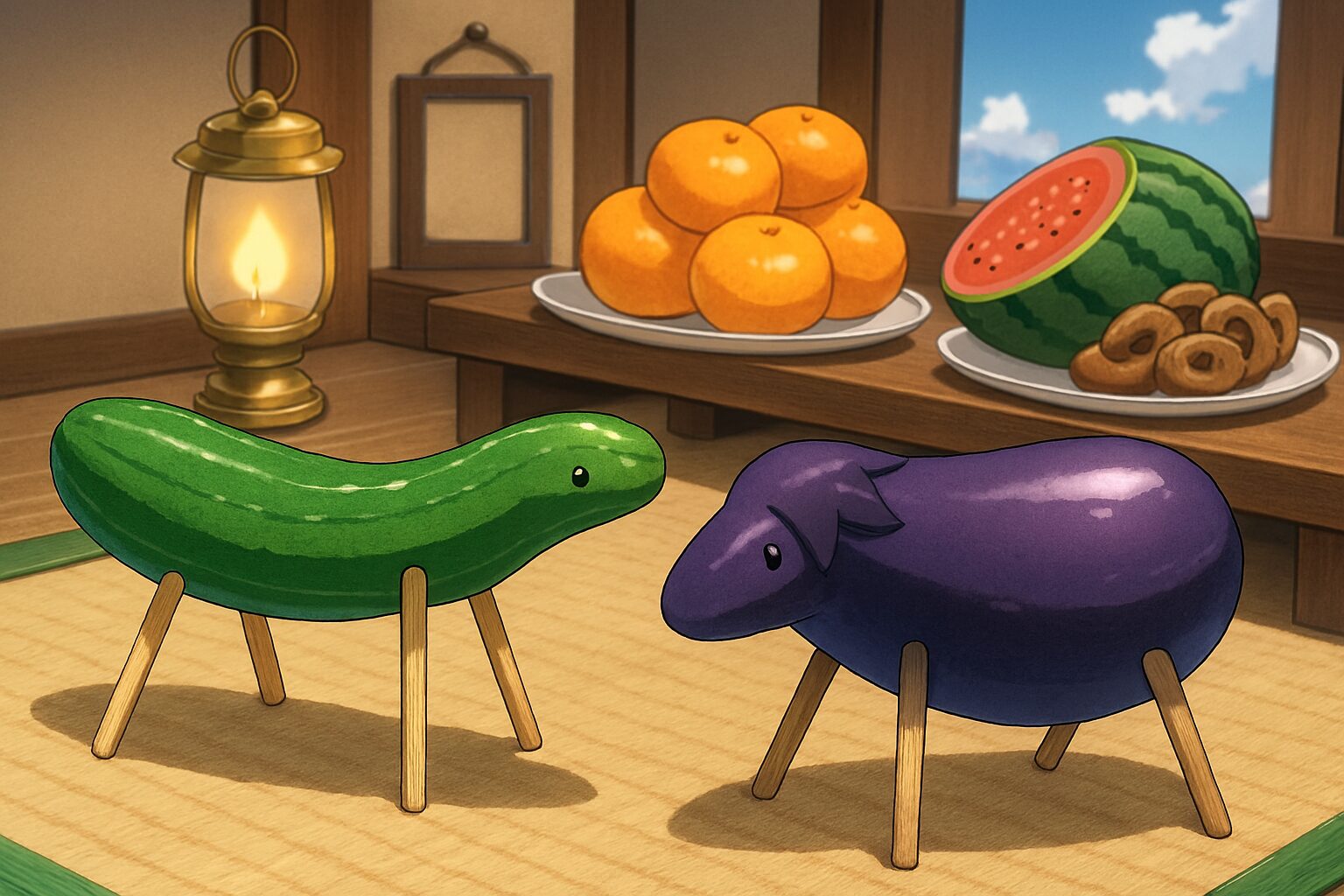

Among the many symbols of Obon, few are as charming—and profound—as the vegetable animals known as Shōryō-uma (spirit horses) and Shōryō-ushi (spirit cows). These are simple creations made by sticking chopsticks or toothpicks into cucumbers and eggplants to form legs, transforming them into symbolic vehicles for ancestral spirits.

| Vegetable | Role | Symbolism |

|---|---|---|

| Cucumber (Horse) | Shōryō-uma | Fast transport to bring ancestors home quickly |

| Eggplant (Cow) | Shōryō-ushi | Slow return, carrying offerings back to the spirit world |

This tradition reflects Japan’s deep sense of hospitality—even toward the dead. It’s not enough to remember them; we must welcome them with care, provide them with transportation, and ensure their journey is smooth and respectful.

🔥 Welcoming and Sending Off: The Fires That Guide the Way

Obon begins with a “mukaebi” (welcoming fire) and ends with an “okuribi” (sending-off fire). These flames serve as spiritual beacons, guiding the spirits to and from the world of the living. Families light lanterns or burn bundles of hemp stalks called “ogara,” believed to purify and protect.

In some regions, the spirit animals themselves are made with ogara legs, adding another layer of meaning to the ritual.

🏡 Where and How to Display Spirit Animals

Spirit horses and cows are typically placed on a “bon-dana” (Obon altar), alongside seasonal fruits, sweets, and the favorite foods of the deceased. Their orientation changes depending on the day:

- August 13 (Arrival): Heads face inward, toward the home.

- August 16 (Departure): Heads face outward, toward the spirit world.

These small details reflect a larger philosophy: that every gesture, no matter how humble, carries spiritual weight.

🧂 What Happens After Obon?

After Obon ends, the spirit animals are respectfully disposed of. They are not eaten, as they’ve served a sacred purpose. Common disposal methods include:

- Sprinkling with salt and wrapping in white paper before discarding

- Burying them in soil to return them to nature

- Bringing them to temples for ceremonial burning

In Edo-period Japan, some merchants even pickled the vegetables and sold them as souvenirs—a curious blend of reverence and commerce.

🌸 The Heart of Obon: Connection Beyond Time

Obon is a time to pause and reflect. It’s a reminder that life is not a straight line, but a circle—where the past, present, and future are always in dialogue. By welcoming our ancestors home, we reaffirm our place in that circle.

For international readers, Obon may seem mysterious. But its core values are universal:

- Family and remembrance

- Respect for nature and the unseen

- The desire to honor those who shaped us

These are not just Japanese ideals—they are human ones.

🧘♂️ Spirituality Beyond Religion

One of the most fascinating aspects of Obon is how deeply spiritual it is, even for people who don’t consider themselves religious. In Japan, many identify as “non-religious,” yet they participate in rituals like Obon with sincerity and reverence. This reflects a unique cultural approach to spirituality—one that values connection, gratitude, and presence over doctrine.

To explore this idea further, check out Japanese Spirituality Explained: Why “Non-Religious” Doesn’t Mean “Unspiritual”. It’s a thoughtful look at how Japanese people engage with the sacred in everyday life.

✨ Conclusion: Why Spirit Horses Still Matter

The cucumber horse and eggplant cow may look like child’s crafts, but they carry centuries of meaning. They are symbols of love, memory, and the enduring bond between the living and the dead.

So if you’re in Japan this summer—or simply curious about its culture—try making a Shōryō-uma. Place it gently on your altar, light a candle, and take a moment to welcome the spirits home. You might just feel the presence of something timeless.

お盆とは何か?精霊馬に込められた日本人の「迎える心」

🌿はじめに:年に一度、ご先祖様が帰ってくる日

日本の夏には、静かで深い祈りの時間があります。それが「お盆(Obon)」です。毎年8月13日から16日までの4日間、多くの家庭では仏壇を整え、墓参りをし、迎え火を焚いてご先祖様をお迎えします。

この行事は単なる宗教儀礼ではなく、「命のつながり」を再確認する時間。日本人の死生観、家族観、そして自然との共生の哲学が凝縮された文化です。

🐴精霊馬(しょうりょううま)と精霊牛(しょうりょううし)とは?

お盆の風景の中で、ひときわユニークな存在が「精霊馬」と「精霊牛」です。キュウリとナスに割り箸を刺して作る、野菜の動物たち。これらは、ご先祖様の霊があの世とこの世を行き来するための「乗り物」とされています。

| 野菜 | 役割 | 意味 |

|---|---|---|

| キュウリ(馬) | 精霊馬 | ご先祖様が早く帰ってこられるように |

| ナス(牛) | 精霊牛 | ゆっくりと、荷物を積んで帰っていただくため |

この発想には、日本人特有の「おもてなし」の心が宿っています。霊を迎えるにあたって、ただ祈るだけでなく、乗り物まで用意する。しかもそれが、身近な野菜で手作りされるという素朴さ。まさに「心を形にする」文化です。

🔥迎え火と送り火:道しるべとしての炎

お盆の始まりには「迎え火」、終わりには「送り火」を焚きます。これは、ご先祖様が迷わず家に帰ってこられるように、そして無事にあの世へ戻れるようにという願いを込めた灯りです。

迎え火には「おがら(麻の茎)」が使われることが多く、魔除けや清浄の意味もあります。精霊馬の脚にもこのおがらが使われることがあり、素材の選び方ひとつにも深い意味が込められています。

🏡飾る場所とタイミング:仏壇と盆棚

精霊馬と精霊牛は、仏壇や「盆棚(精霊棚)」に飾ります。盆棚は、ご先祖様を迎えるための特設祭壇で、季節の果物や故人の好物などと一緒に供えられます。

- 飾る期間:8月13日〜16日(地域によっては7月盆もあり)

- 向き:

- 迎え盆(13日):頭を家の内側に向ける

- 送り盆(16日):頭を外側に向ける

地域や宗派によっては飾らない場合もあります。たとえば浄土真宗では、霊が行き来するという考え方をとらないため、精霊馬を作らないこともあります。

🧂処分方法:感謝と清めの心を込めて

お盆が終わった後の精霊馬は、基本的に食べません。ご先祖様の乗り物として使ったものなので、敬意を込めて処分します。

- 塩で清めて白紙に包み、可燃ごみへ

- 庭やプランターに埋めて土に還す

- お寺で焚き上げ供養してもらう

江戸時代の豪商・河村瑞賢は、精霊馬を塩漬けにして保存し、漬物として販売したという逸話も残っています。命を敬う心と、生活の知恵が共存する、なんとも日本らしいエピソードです。

🌸お盆の本質:命のつながりを感じる時間

お盆は、忙しい日常から離れて、静かに命のつながりを感じる時間です。仏壇に手を合わせ、故人の思い出を語り合うことで、私たちは「今ここに生きている意味」を再確認します。

海外の方にとっては、少し不思議に映るかもしれません。でもこの風習には、普遍的な価値があります。

- 家族を思う心

- 自然と共に生きる知恵

- 目に見えないものへの敬意

これらは、国境を越えて人々の心に響くものです。

✨まとめ:精霊馬に込められた「迎える心」

精霊馬は、ただの飾りではありません。それは、ご先祖様を迎えるための「心のかたち」。キュウリとナスに割り箸を刺すという素朴な行為の中に、日本人の死生観とおもてなしの哲学が宿っています。

今年のお盆は、ぜひ精霊馬を手作りしてみてください。そして、その意味を知ったうえで飾ることで、ただの行事が「心を込めた迎えの儀式」へと変わるはずです。

コメント