In the Japanese calendar, February 10th is not just another winter day. On this day in 1988, the Japanese archipelago was literally cast under a “spell.” Students vanished from schools, employees disappeared from offices, and lines stretching for kilometers formed in front of electronics stores.

The cause was a single video game: “Dragon Quest III: The Seeds of Salvation” (Soshite Densetsu e…).

Today, let’s dive deep into this legendary day that rewrote the history of Japanese pop culture and pushed video games from “children’s toys” to a massive “social phenomenon.”

February 10, 1988: What Happened?

In the late 1980s, Japan was standing at the entrance of the “Bubble Economy.” Amidst this, Nintendo’s Family Computer (known as the NES overseas) reigned supreme in home entertainment. The “Dragon Quest” series, released by Enix (now Square Enix), was already permeating society.

However, the release of the third installment, “Dragon Quest III,” created an extraordinary situation that overturned all conventional wisdom.

Queues Requiring Police Intervention

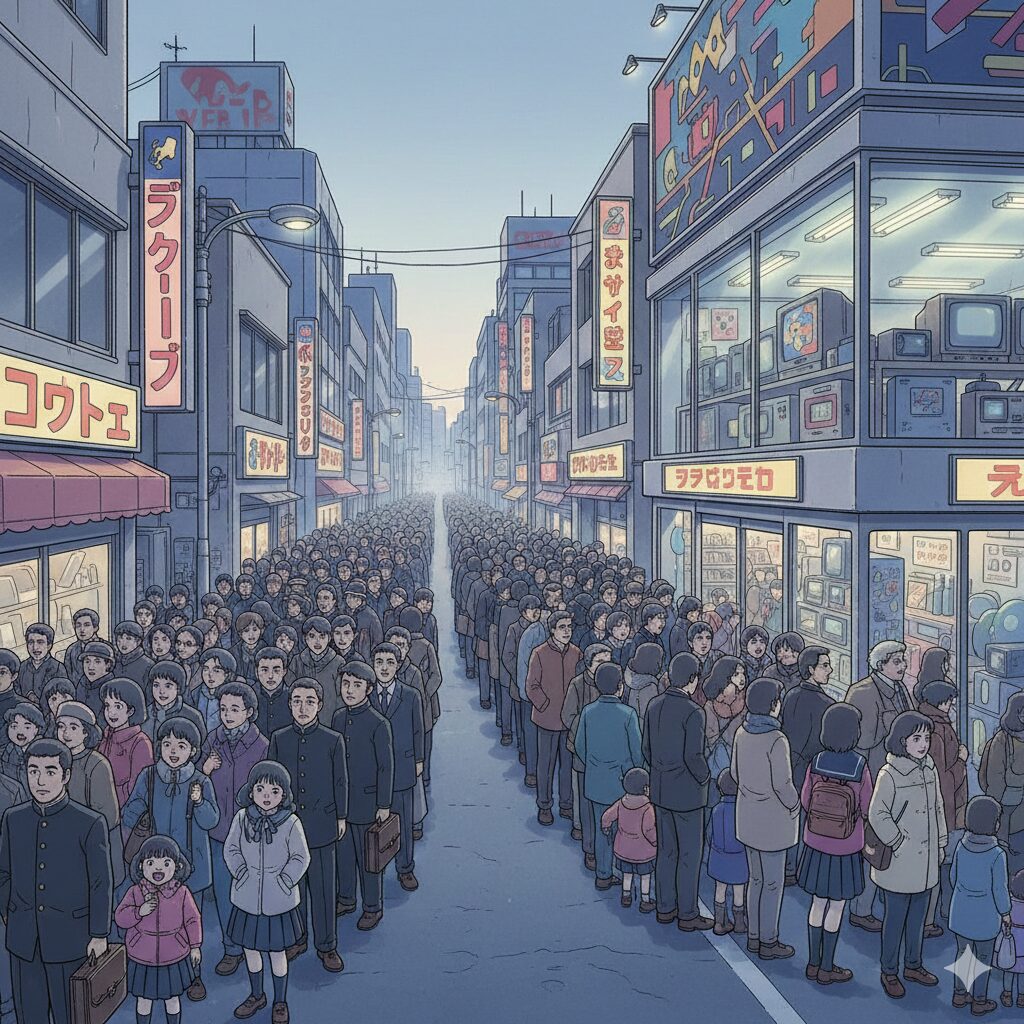

On the day of release, thousands, if not tens of thousands, of people lined up overnight at electronics stores in major cities like Ikebukuro and Shinjuku in Tokyo, and Nipponbashi in Osaka. It is estimated that nearly 100,000 people were queuing nationwide. In an era before internet pre-orders existed, the only way to get a copy was to stand in line.

The term “Dragon Quest Hunting” (Doraque-gari) made the news. The game was so popular that incidents of muggings—where older youths would threaten and steal the game from children who had just bought it—occurred frequently. This was no longer just a hit product; it was a social issue.

“Dragon Quest Truancy” and the Ban on Weekday Releases

February 10, 1988, was a Wednesday. A weekday. Yet, on this day, elementary, junior high, and high schools across the country saw a surge of students being taken into protective custody by police for truancy or skipping school entirely. Even adults were seen feigning illness to skip work and join the lines.

The chaos was so severe that it reportedly led to an unwritten rule (later an industry custom) that future Dragon Quest titles would only be released on “Saturdays, Sundays, or National Holidays.” It was the moment a single game impacted Japan’s logistics, labor, and educational environments.

Why Did “Dragon Quest III” Become a Legend?

A merely “popular game” would not cause such a phenomenon. Why were Japanese people so fanatical about this title? There were three “revolutions” involved.

1. Character Creation and “Luida’s Bar”

In previous titles, the protagonist was alone or traveled with fixed companions. In this installment, however, players could visit “Luida’s Bar” to choose companions from classes like Warrior, Mage, Priest, or Gadabout, and form their own party.

This meant players could weave “their own story.” By naming characters after school friends or favorite idols, immersion skyrocketed.

2. A Shocking Scenario Connecting Two Worlds

*Contains mild spoilers, but essential for historical context.*

The meaning of the subtitle “The Seeds of Salvation” (And into the Legend…) is revealed the moment the game is cleared. The ending unveils that this story is actually a prequel to the first and second games, and the player themselves becomes the legendary hero “Loto” (Erdrick).

This plot twist gave Japanese children at the time goosebumps. It was the moment a standalone work was completed as a grand epic saga.

3. The Golden Triangle: Toriyama, Sugiyama, and Horii

Akira Toriyama, world-famous for Dragon Ball, provided the character design. Koichi Sugiyama brought the gravity of classical music to game sound. And Yuji Horii invented warm, relatable dialogue that anyone could understand.

“Dragon Quest III” was where the talents of these three masters fused perfectly. Furthermore, the “Battery Backup” feature allowed players to save their progress without writing down long passwords (though the cursed music when save data vanished remains a collective trauma), enabling a longer, deeper adventure.

Reading the “Immersion in RPGs” Through Japanese Culture

This event reveals interesting aspects of Japanese national character and culture.

The Aesthetics of “Diligent Effort” (Kotsu-Kotsu)

The “Grinding” (level-up process) characteristic of JRPGs is deeply connected to Japanese views on labor and learning. The structure where “even simple tasks, if performed diligently over time, will surely be rewarded (you become stronger)” mirrors the agrarian mindset and aligned with the Japanese education system of the time. Dragon Quest was a pleasure device where effort was visualized.

The Shared Experience of “The Queue”

Japanese people generally do not mind queuing as much as others might. In fact, the massive lines on February 10th were like a “Festival” (Matsuri). Standing for hours in the cold for the same purpose creates a strange sense of solidarity among strangers. The experience of “overcoming this hardship to obtain the prize” served as a prologue to the gameplay itself.

What is Your “Legend”?

On February 10, 1988, Japan was certainly under a gaming spell. It might have been the first singularity where the digital world surpassed the real world.

In modern times, games can be downloaded instantly. There is no need to wait for a store to open while shivering under the midwinter sky. However, the heat of that moment, the weight of the physical package, and the excitement of opening the instruction manual seem like treasures found only in that inconvenience.

I want to ask you, the readers:

What is the one thing in your life you passionately pursued to obtain? If the sequel to your favorite game were released today, would you be prepared to queue outside in freezing temperatures for 24 hours?

Please tell us about game release episodes in your country or your own personal “legend” in the comments below.

Related Links:

- Dragon Quest Official Site (SQUARE ENIX)

- What’s Today’s Special Day Series – See more Japanese special days

2月10日:日本が止まった日。伝説のRPG『ドラゴンクエストIII』が変えたもの

日本のカレンダーにおいて、2月10日は単なる冬の一日ではありません。1988年のこの日、日本列島は文字通り「魔法」にかかりました。学校から生徒が消え、会社から従業員がいなくなり、家電量販店の前には数キロメートルに及ぶ行列ができたのです。

その原因はたった一つのビデオゲーム。『ドラゴンクエストIII そして伝説へ…』です。

今日は、日本のポップカルチャーの歴史を塗り替え、ビデオゲームを「子供の遊び」から「社会現象」へと押し上げた、伝説の一日について深く掘り下げていきましょう。

1988年2月10日:何が起きたのか?

1980年代後半、日本はバブル景気の入り口に立っていました。そんな中、任天堂のファミリーコンピュータ(海外ではNES)は、日本の家庭における娯楽の覇者となっていました。そして、エニックス(現スクウェア・エニックス)が世に送り出した『ドラゴンクエスト』シリーズは、すでに社会に浸透しつつありました。

しかし、3作目となる『ドラゴンクエストIII』の発売日は、これまでの常識を覆す異常事態となりました。

警察が出動するほどの行列

発売当日、東京の池袋や新宿、大阪の日本橋など、主要都市の電気店には、前夜から徹夜組を含む数千、数万人の行列ができました。その数は全国で推定数万人とも言われています。当時はインターネット予約など存在しない時代。手に入れるには、店に並ぶしかなかったのです。

「ドラクエ狩り」という言葉がニュースになりました。あまりの人気に、購入したばかりのソフトをカツアゲされる(脅し取られる)少年たちが続出したのです。これは単なるヒット商品ではなく、社会問題でした。

「ドラクエ休暇」と平日発売の禁止

1988年2月10日は水曜日でした。平日です。しかし、この日、全国の小中学校や高校で、補導される生徒や、無断欠席する生徒が相次ぎました。さらには、社会人でさえも「風邪」と偽って会社を休み、行列に並ぶ姿が見られました。

あまりの混乱ぶりに、この出来事以降、ドラゴンクエストの新作発売日は「土曜日または日曜日、祝日」に設定されるという不文律(のちに業界の慣習)が生まれたほどです。一つのゲームが、日本の流通システムと労働・教育環境に影響を与えた瞬間でした。

なぜ『ドラゴンクエストIII』は伝説になったのか?

単なる「人気ゲーム」であれば、ここまでの現象にはなりません。なぜ日本人はこれほどまでにこのゲームに熱狂したのでしょうか。そこには3つの「革命」がありました。

1. キャラクターメイキングと「ルイーダの酒場」

前作まで、主人公は孤独、あるいは固定された仲間と旅をしていました。しかし今作では「ルイーダの酒場」で、戦士、魔法使い、僧侶、遊び人など、自分の好きな職業の仲間を選び、名前を付けてパーティを組むことができました。

これは、プレイヤーが「自分だけの物語」を紡ぐことができるようになったことを意味します。学校の友達の名前を付けたり、好きなアイドルの名前を付けたりすることで、没入感は爆発的に高まりました。

2. 二つの世界をつなぐ衝撃のシナリオ

※ネタバレを含みますが、歴史的文脈として重要です。

『ドラゴンクエストIII』のサブタイトル「そして伝説へ…」の意味は、ゲームをクリアした瞬間に判明します。この物語が、実は第1作、第2作の「過去の物語」であり、プレイヤー自身が、伝説の勇者「ロト」になるという結末です。

このどんでん返しは、当時の日本の子供たちに鳥肌が立つほどの感動を与えました。単発の作品が、壮大な叙事詩(サーガ)として完成した瞬間でした。

3. 鳥山明、すぎやまこういち、堀井雄二の黄金トライアングル

『ドラゴンボール』で世界的に有名な鳥山明氏によるキャラクターデザイン、クラシック音楽の重厚さをゲーム音楽に持ち込んだすぎやまこういち氏、そして、誰もが理解できる温かみのあるセリフ回しを発明した堀井雄二氏。

この3人の才能が完全に融合したのが『III』でした。特に、カートリッジに搭載された「バッテリーバックアップ」機能により、長い呪文(パスワード)をノートにメモする必要がなくなり(ただし、セーブデータが消える時の呪いの音楽はトラウマですが)、より長く、深い冒険が可能になったのです。

日本文化から読み解く「RPGへの没入」

この出来事から、日本人の国民性や文化について興味深い側面が見えてきます。

「コツコツ努力」の美学

JRPG(日本のロールプレイングゲーム)の特徴である「レベル上げ(Grinding)」は、日本人の労働観や学習観と深く結びついています。「単純な作業であっても、時間をかけて努力を積み重ねれば、必ず報われる(強くなる)」という構造は、農耕民族的であり、当時の日本の教育システムとも合致していました。ドラクエは、努力が可視化される快感装置だったのです。

「行列」という共感体験

日本人は行列に並ぶことをそれほど嫌がりません。むしろ、2月10日の大行列は「お祭り(Festival)」でした。寒空の下、同じ目的のために何時間も並ぶことで、見知らぬ人同士の中に奇妙な連帯感が生まれます。「この辛さを乗り越えて手に入れた」という体験自体が、ゲームプレイの前のプロローグとなっていたのです。

あなたにとっての「伝説」は何ですか?

1988年2月10日、日本は確かにゲームの魔法にかかっていました。それは、デジタルの世界が現実の世界を凌駕した最初の特異点だったのかもしれません。

現代では、ゲームはダウンロードで瞬時に手に入ります。真冬の空の下、震えながら開店を待つ必要はありません。しかし、あの時の熱気、手に入れたパッケージの重み、そして取扱説明書を開くときの高揚感は、不便さの中にこそあった宝物のような気がします。

読者の皆さんに問いかけたいと思います。

あなたが人生で一番情熱を注いで手に入れたものは何ですか? もし今、あなたが一番好きなゲームの続編が出るとして、氷点下の屋外で24時間並ぶ覚悟はありますか?

ぜひ、あなたの国のゲーム発売日のエピソードや、あなたの「伝説」についてコメントで教えてください。

関連リンク:

コメント