Category: Japanese Folktale Series

The Japanese archipelago, blessed with four distinct seasons and rich, fertile soil, has nourished a culture where reverence for nature and its bounty is deeply ingrained. From this agrarian foundation, countless stories—mukashibanashi—have been spun, passing down practical wisdom and moral lessons through the generations. Among these, the seemingly simple tale of Ninjin to Gobo to Daikon (Carrot, Burdock Root, and Daikon Radish), stands as a profound exploration of human—or rather, vegetable—nature, envy, and the ultimate realization of one’s true, inherent worth.

This is not just a children’s story; it is a mirror reflecting the delicate balance between appearance and essence that permeates Japanese aesthetics and philosophy.

- Part I: The Tale of the Carrot, the Burdock Root, and the Daikon Radish (Ninjin to Gobo to Daikon)

- Part II: A Deep Dive into the Roots of the Tale (Folktale Analysis)

- Part III: Connecting the Roots to Japanese Culture (Cultural Ties)

- Part IV: Pondering the Roots of Human Nature

- External and Internal References

- パートI:にんじんとごぼうとだいこんの物語

- パートII:物語のルーツを深く掘り下げる(昔話の考察)

- パートIII:根菜と日本文化のつながり(日本文化との関連)

- パートIV:人間の本質の根源を考える

- 外部リンクと内部リンク

Part I: The Tale of the Carrot, the Burdock Root, and the Daikon Radish (Ninjin to Gobo to Daikon)

The Three Proud Roots

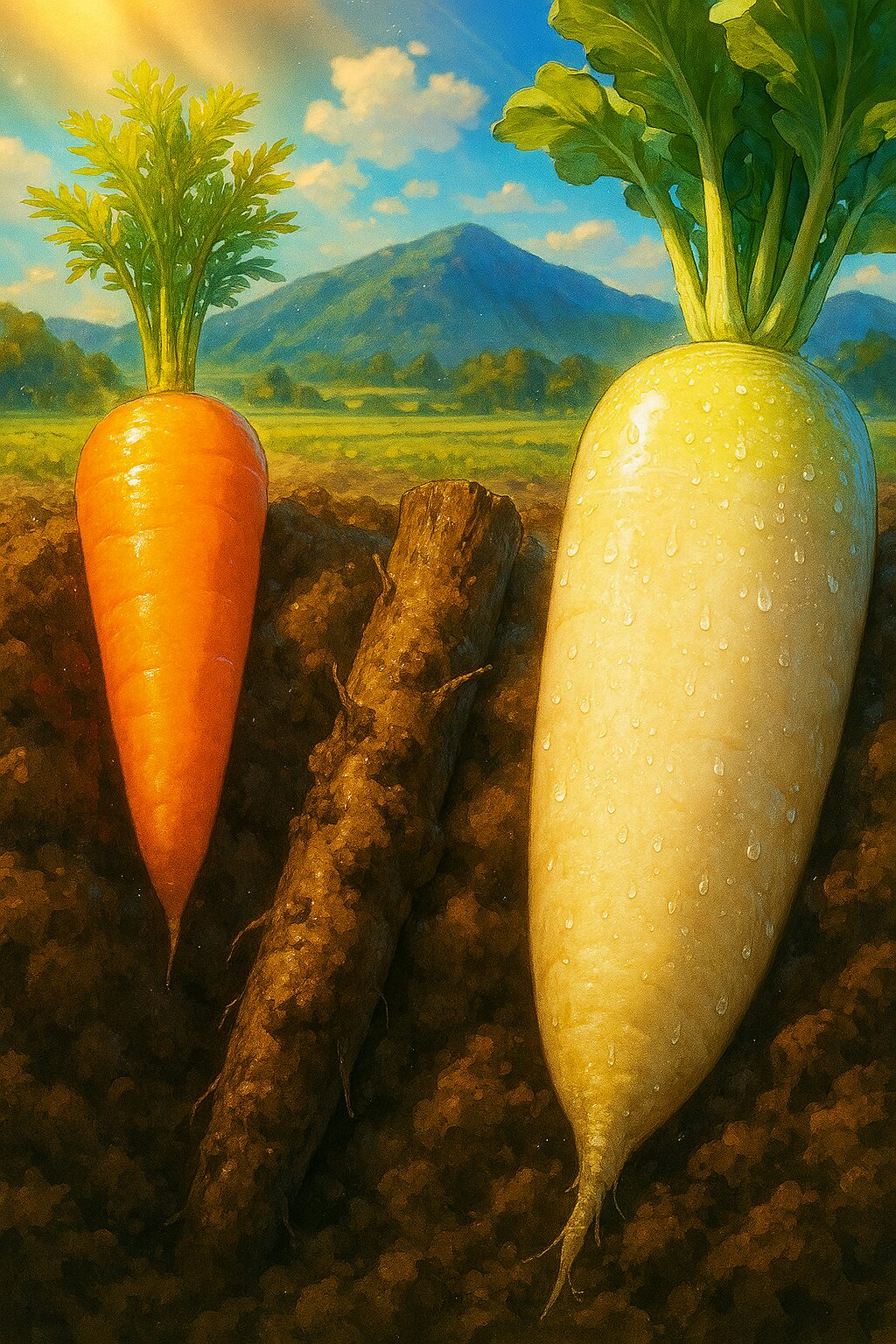

Once upon a time, deep beneath the rich, dark soil of a Japanese field, lived three close companions: Ninjin (The Carrot), Gobo (The Burdock Root), and Daikon (The Daikon Radish). Each was an essential part of the Japanese diet, yet each possessed a distinctly different character.

Ninjin, the Carrot, was the proudest of the three. He was boastful of his vibrant, sunset-orange skin, smooth and unblemished. “Look at me!” he would exclaim. “I am the color of the rising sun, and my skin is as sleek as silk. When I am pulled from the ground, I am ready for the pot immediately. No need for scrubbing or preparation!”

Gobo, the Burdock Root, was dark and earthy, covered in rough, brown, soil-stained skin. He often felt a sting of envy and resentment towards Ninjin. “Your smoothness means nothing,” Gobo would mutter darkly. “I am strong and long, enduring the deep earth. But alas, I must be scraped and scrubbed, and my skin must be peeled away before I am deemed worthy.”

Daikon, the Daikon Radish, was stout and pure white, with a thick, satisfying crunch. He was generally good-natured but held a quiet worry. His skin, though white, was sometimes speckled with small marks from the soil. “I am worried about being peeled,” he would confess. “I have heard that those who are peeled suffer a terrible, painful fate.”

The Fearful Day of the Harvest

One blustery autumn day, the earth above them trembled, and the sound of the farmer’s hoe filled them with dread. It was the day of the harvest.

First, Ninjin was grasped and yanked from the soil. He emerged, radiating his glorious orange hue. The farmer merely brushed the loose dirt from him and placed him gently in the basket. Ninjin swelled with pride. “See, friends?” he shouted down into the hole. “I am perfect! I was not washed, I was not scraped! My perfection saves me from such indignity!”

Next came Gobo. The farmer had to pull harder, wrenching the long, tenacious root from the ground. Gobo, covered in stubborn, cloying dirt, was thrown onto a rough washing mat. The farmer took a stiff brush and violently scrubbed Gobo’s skin. Gobo cried out in pain and humiliation as his dark skin was scraped and peeled away until his inner white flesh was exposed. His envy turned to bitter despair.

Finally, it was Daikon’s turn. He was pulled out, thick and heavy. Remembering Gobo’s suffering, Daikon was seized by a terrible fear of the scrubbing brush. “Oh, no! They will peel me too!” he lamented. The fear was so intense that as the farmer prepared to scrub him, Daikon was overcome, and his smooth, white skin broke out in a cold, oily sweat.

The farmer, seeing the thick, clear liquid covering the Daikon’s skin, frowned. “This Daikon seems to be sweating up a storm,” he commented. He wiped the liquid away with his rough hand, but the sweat continued to bead. Thinking the Daikon was not fresh, the farmer roughly chopped off the root and the leaves and simply placed the large, still-sweating Daikon into the basket, only needing a light rinse before being ready for market. Daikon was spared the pain of the scraping brush.

The Enduring Lesson

In the basket, the three roots lay together.

- Ninjin, still boasting, felt the heat of the sun and realized his unblemished skin was soft and thin. He felt his color fading slightly.

- Gobo, now pale and scraped, looked upon his own reflection in a drop of water and saw only a raw, wounded surface. His bitterness remained.

- But Daikon, who had feared the scrubbing most, looked down and saw his entire body was covered in a cold, oily sweat—a sweat of pure, unadulterated fear. He realized that his outward appearance was forever marked by his profound lack of courage.

And so, even to this day, the story says:

- Ninjin has beautiful, smooth skin because he was once so proud and escaped the scrubbing.

- Gobo must be vigorously scraped before he can be eaten because he was once so jealous and complained about his appearance.

- Daikon always has a faint oily sheen on his skin because he once sweated from fear, and this mark of cowardice remains forever.

Part II: A Deep Dive into the Roots of the Tale (Folktale Analysis)

This seemingly simple agricultural allegory, beloved across Japan, is a masterclass in moral storytelling. As a programmer, I approach this story not just as a narrative, but as an algorithm for life—a set of inputs (pride, envy, fear) leading to fixed, irreversible outputs (the physical characteristics of the vegetables).

1. The Power of “Origin Stories” (Etiology and Behavior)

The most striking feature of the tale is its use of etiology, the explanation of a natural phenomenon. The story serves to explain the observable reality of how these three common Japanese vegetables must be prepared:

- Carrot (Ninjin): Needs minimal scrubbing (output of pride/perfection).

- Burdock Root (Gobo): Needs heavy scraping (output of resentment/scrutiny).

- Daikon Radish (Daikon): Has a waxy, oily surface (output of fear/cowardice).

In traditional Japanese storytelling, giving a tangible, physical consequence to a moral failing makes the lesson stick. The consequences of their internal attitudes are made permanent and external—a stark and uncompromising judgment.

2. The Critique of Appearance vs. Essence

The tale is a direct challenge to vanity and superficial judgment. Ninjin’s pride is based entirely on his skin (appearance), which the story ultimately suggests is fragile and thin. Gobo’s envy is rooted in the belief that his dark, rough skin makes him “less worthy.”

In the end, it is not the external appearance that defines the fate, but the internal attitude. Gobo’s constant complaining (envy) resulted in a painful punishment (scraping). Daikon’s paralyzing fear (cowardice) left a permanent, humiliating mark (the sweat). The moral is not about the color of the skin, but the character within. The roots, the core of the vegetable, represent the core of a person.

3. The Uncompromising Nature of Justice

Unlike many Western fables where lessons are learned and characters are redeemed, the ending of Ninjin to Gobo to Daikon is uncompromisingly fixed. The consequences are eternal, manifested in their very being. This reflects a strain of traditional Japanese thought where actions—especially those driven by negative emotions like envy (netami) or vanity (maneshigokoro)—have immediate, lasting, and sometimes karmic repercussions. The punishment is not arbitrary; it is a logical, physical manifestation of the root’s emotional flaw.

Part III: Connecting the Roots to Japanese Culture (Cultural Ties)

This simple tale of three roots offers deep insights into core values and aesthetics that define Japanese culture, from its cuisine to its social structure.

1. Wabi-Sabi and the Perfection of Imperfection

Ninjin’s downfall is his pursuit of external perfection. Japanese aesthetics, particularly Wabi-Sabi, find beauty in the imperfect, the ephemeral, and the rustic.

- Gobo, though scraped, embodies the wabi spirit: rustic, humble, and enduring. His earthy flavor is highly prized in dishes like Kimpira Gobo, where its shakishaki (crisp) texture is celebrated. The act of scraping and preparing Gobo is a necessary, almost ritualistic, process—a reminder that value often requires effort.

- Ninjin‘s “perfection” is fleeting, fading in the sun. This reinforces the Buddhist concept of **Mujo (無常)**, the impermanence of all things. True beauty is not in the flawless, but in the enduring quality of the spirit, something Ninjin lacked.

2. Social Harmony and Group Dynamics (Wa – 和)

The dynamic between the three roots is a micro-cosmos of traditional Japanese social structure, where Wa (和 – harmony) is paramount.

- The story subtly critiques those who disrupt harmony: Ninjin through boastfulness (excessive ego) and Gobo through envy (resentment towards the group). In a society that values collective unity, drawing undue attention to oneself or harboring negative feelings towards others is a social transgression.

- The emphasis on preparation (washing, scraping) speaks to the concept of **Omotenashi (おもてなし)**, selfless hospitality. The effort required to clean Gobo is a task the Japanese embrace because the final taste justifies the effort. The story suggests that some people (or roots) simply require more work to be appreciated, but that work is a part of their value.

3. The Importance of the Soil (The Land and Agriculture)

These three roots are fundamental to Washoku (和食 – traditional Japanese cuisine), particularly Nimono (simmered dishes) and Kenchinjiru (vegetable soups). The fact that the story is set underground emphasizes the profound connection between the Japanese people and the land.

The tale teaches respect for the source of food and the effort required to cultivate it. By personifying the vegetables, the story elevates them from mere ingredients to characters with dignity, encouraging appreciation for the earth’s yield—a core tenet of Shintoism and the agrarian lifestyle that shaped Japan.

Part IV: Pondering the Roots of Human Nature

The tale of “The Carrot, The Burdock Root, and The Daikon Radish” remains a relevant and powerful piece of wisdom literature. It offers a concise, unforgettable lesson that transcends time and culture.

The enduring truth of this story is that our internal attitudes—pride, envy, and fear—are never truly hidden. They manifest as our external reality, whether as an unearned appearance of perfection, a lifetime of painful correction, or a persistent, cold sweat of anxiety.

To our readers across the globe, what do you take away from the fate of Ninjin, Gobo, and Daikon?

- Which root’s flaw do you find most relatable in your own life or modern society? Is it Ninjin’s superficial pride, Gobo’s bitter envy, or Daikon’s paralyzing fear?

- If you could speak to Daikon, what advice would you offer him to overcome his fear?

- How does this story change the way you look at the humble vegetables on your dinner plate?

Share your thoughts in the comments below! Let the conversation unearth new depths of this ancient wisdom.

External and Internal References

[Internal Category Link]

[External Reference Links]

- Japanese Culinary Culture: The Role of Root Vegetables in Washoku (A guide to Japanese cuisine and core ingredients.)

🥕 三つの根菜が教える人生の教訓:「にんじんとごぼうとだいこん」の深い話 🇯🇵

カテゴリー:日本の昔話シリーズ

四季に恵まれ、豊かな大地を持つ日本列島は、自然とその恵みに対する敬意が深く根付いた文化を育んできました。この農耕文化の土台から、数え切れないほどの物語、すなわち「昔話(むかしばなし)」が紡ぎ出され、世代を超えて実践的な知恵や道徳的な教訓が伝えられてきました。その中でも、一見すると単純な「にんじんとごぼうとだいこん」の物語は、人間の、いや、根菜たちの本質、嫉妬、そして真の内在的価値の究極的な認識を探求する奥深い物語として存在しています。

これは単なる子ども向けのお話ではありません。それは、日本の美意識や哲学に深く浸透している「外見と本質」のデリケートなバランスを映し出す鏡なのです。

パートI:にんじんとごぼうとだいこんの物語

三つの誇り高き根菜たち

むかしむかし、日本の畑の肥沃で暗い土の中に、三つの仲良しな根菜、にんじん、ごぼう、そしてだいこんが暮らしていました。彼らは皆、日本の食卓に欠かせない存在でしたが、それぞれが全く異なる性格を持っていました。

中でも**にんじん**は、三匹の中で最も自慢屋でした。彼は、夕日のような鮮やかなオレンジ色の皮、滑らかで傷一つない肌を鼻にかけていました。「私を見てごらん!」と彼は自慢します。「私は昇る太陽の色をしていて、肌は絹のようにツヤツヤだ。土から引き抜かれたら、すぐに鍋に入れることができる。洗ったり、準備したりする必要など全くないのだよ!」

**ごぼう**は、黒っぽく土臭い、ザラザラした茶色の土に汚れた皮で覆われていました。彼は、にんじんに向けてしばしば嫉妬と恨みの念を抱いていました。「お前の滑らかさなど何の意味もない」とごぼうは暗くつぶやきます。「私は強くて長く、深い土の中で耐え忍んでいる。だが、ああ、私は価値あるものと見なされる前に、削られ、こすられ、皮を剥ぎ取られなければならないのだから!」

**だいこん**は、太くて純白で、シャキシャキとした満足感のある歯ごたえを持っていました。彼は概ね朗らかな性格でしたが、ひそかに一つの心配を抱えていました。彼の白い肌には、時折土からの小さな斑点がついていたのです。「皮を剥かれるのが心配だ」と彼は打ち明けました。「皮を剥かれた者は、恐ろしく痛い目に遭うと聞いているから。」

恐怖の収穫の日

ある肌寒い秋の日、彼らの上の土が震え、農夫の鍬の音が恐怖で彼らを満たしました。収穫の日が来たのです。

最初に、**にんじん**が掴まれ、土から引き抜かれました。彼は栄光に満ちたオレンジ色の輝きを放ちながら現れました。農夫は、彼についたゆるい土を軽く払い落としただけで、優しくかごに入れました。にんじんは誇りでいっぱいになりました。「見たかね、友よ?」と彼は穴の中に叫びました。「私は完璧だ!洗われることも、削られることもなかった!私の完璧さが、そのような屈辱から私を救ったのだ!」

次に**ごぼう**の番です。農夫は、長くしぶとい根を地面から引き抜くため、より強く引っ張らなければなりませんでした。しつこい泥にまみれたごぼうは、荒い洗い場の上に投げ出されました。農夫は硬いブラシを取り、ごぼうの皮を激しくこすりつけました。ごぼうは、内側の白い肉が露出するまで黒い皮が削り取られ、痛みと屈辱に泣き叫びました。彼の嫉妬は、苦い絶望へと変わりました。

最後に、**だいこん**の番です。彼は太く重く引き抜かれました。ごぼうの苦しみを思い出し、だいこんはたわしへの恐ろしい恐怖に襲われました。「ああ、だめだ!私も剥かれてしまう!」と彼は嘆きました。その恐怖があまりにも強かったため、農夫が彼をこすろうと準備した瞬間、だいこんは恐怖に打ちのめされ、彼の滑らかな白い肌から**冷たい油のような汗が噴き出したのです。**

農夫は、だいこんの肌を覆う濃い透明な液体を見て、顔をしかめました。「このだいこんはひどく汗をかいているようだ」と彼はコメントしました。彼は荒い手で液体を拭き取りましたが、汗は滴り続けました。だいこんが新鮮ではないと考えた農夫は、乱暴に根と葉を切り落とし、軽くすすぐだけで市場に出せる、その大きく、汗をかき続けているだいこんをかごに置きました。だいこんは、削られる痛みから解放されたのです。

永遠の教訓

かごの中で、三つの根菜は一緒に横たわりました。

- 誇らしげだった**にんじん**は、太陽の熱を感じ、傷一つない皮が柔らかく薄いことに気づきました。彼は自分の色がわずかに色褪せていくのを感じました。

- 今や青白く削られた**ごぼう**は、水滴に映った自分の姿を見て、ただ生々しい傷ついた表面を見ました。彼の苦い気持ちは残ったままでした。

- しかし、最もこすられることを恐れた**だいこん**は、自分の全身が、純粋で混じりけのない恐怖の汗である冷たい油のような汗で覆われているのを見下ろしました。彼は、自分の外見が、深い勇気の欠如によって永遠に刻印されてしまったことを悟ったのです。

そして、今日に至るまで、この物語は語り継がれています。

- **にんじん**は、かつてあまりにも傲慢で、こすられることから逃れたため、美しい滑らかな皮を持っています。

- **ごぼう**は、かつてあまりにも嫉妬深く、自分の外見について不平を言ったため、食べられる前に激しく削られなければなりません。

- **だいこん**は、かつて恐怖で汗をかいたため、常に皮膚に微かな油状の光沢があり、この臆病の印が永遠に残っているのです。

パートII:物語のルーツを深く掘り下げる(昔話の考察)

この一見シンプルな農業寓話は、日本中で愛され続けている道徳的な物語の傑作です。プログラマーとして、私はこの物語を単なる物語としてではなく、**「人生のアルゴリズム」**として捉えます。つまり、入力(プライド、嫉妬、恐怖)が、固定的で不可逆な出力(野菜の物理的特性)につながる一連の法則です。

1. 「起源の物語」の力(語源と行動)

この物語の最も印象的な特徴は、自然現象を説明するための「語源論(エティオロジー)」の使用です。この物語は、これら三つの一般的な日本の野菜がどのように準備されなければならないかという観察可能な現実を説明する役割を果たしています。

- **にんじん:** 最小限の洗浄で済む(プライド/完璧さの出力)。

- **ごぼう:** 激しく削る必要がある(恨み/精査の出力)。

- **だいこん:** 蝋のような油性の表面を持つ(恐怖/臆病の出力)。

日本の伝統的な物語では、道徳的な失敗に具体的で物理的な結果を与えることで、教訓を定着させます。彼らの*内面的な*態度の結果は、永続的で*外見的な*ものとなり、容赦のない厳しい判断として現れるのです。

2. 外見と本質の批評

この物語は、虚栄心と表面的な判断に対する直接的な批判です。にんじんの誇りは、その**皮(外見)**に完全に依存していますが、物語は最終的にそれが脆く薄いことを示唆しています。ごぼうの嫉妬は、彼の**暗く荒い皮**が彼を「価値のないもの」にしているという信念に根ざしています。

結局のところ、運命を決定するのは外見ではなく、**内面的な態度**です。ごぼうの絶え間ない不満(嫉妬)は、痛みを伴う罰(削り取り)をもたらしました。だいこんの麻痺するような恐怖(臆病)は、永続的で屈辱的な印(汗)を残しました。教訓は皮の色ではなく、内面にある人柄についてです。野菜の「根」、すなわち核心は、人間の核心を象徴しています。

3. 妥協のない正義の性質

教訓が学ばれ、登場人物が償われる多くの西洋の寓話とは異なり、『にんじんとごぼうとだいこん』の結末は**容赦なく固定的**です。その結果は永遠であり、彼らの存在そのものに現れています。これは、嫉妬(ねたみ)や虚栄心(まねしごころ)のような否定的な感情に駆られた行動が、即座に、永続的に、そして時にはカルマ的な報いをもたらすという、伝統的な日本の思想の傾向を反映しています。罰は恣意的なものではなく、根菜の感情的な欠陥の論理的かつ物理的な現れなのです。

パートIII:根菜と日本文化のつながり(日本文化との関連)

この三つの根菜の単純な物語は、日本の料理から社会構造に至るまで、日本文化を定義する核となる価値観や美意識に対する深い洞察を提供します。

1. 侘び寂びと不完全性の美

にんじんの破滅は、彼が外見的な完璧さを追求したことにあります。日本の美学、特に**侘び寂び(Wabi-Sabi)**は、不完全なもの、儚いもの、そして素朴なものの中に美しさを見出します。

- 削られたとはいえ、**ごぼう**は、素朴で謙虚で、耐え忍ぶわびの精神を体現しています。彼の土の風味は、*きんぴらごぼう*のような料理で高く評価され、そのシャキシャキとした食感が称賛されます。ごぼうを削って準備する行為は、必要不可欠で、ほとんど儀式的なプロセスです。それは、価値を得るには努力が必要であるという教訓でもあります。

- **にんじん**の「完璧さ」はつかの間で、太陽の下で色褪せていきます。これは、仏教の概念である**無常(むじょう)**、すなわち万物の無常性を補強します。真の美しさは、欠陥のないところにあるのではなく、にんじんには欠けていた精神の永続的な資質にあるのです。

2. 社会的調和と集団力学(和 – Wa)

三つの根菜の間の力学は、**和(わ – 調和)**が最も重要視される伝統的な日本の社会構造の小宇宙です。

- この物語は、調和を乱す者を暗に批判しています。**にんじん**は自慢(過度なエゴ)によって、**ごぼう**は嫉妬(集団への恨み)によって、調和を乱しました。集団の統一性を重んじる社会において、自分自身に不当な注意を引いたり、他者に対して否定的な感情を抱いたりすることは、社会的な逸脱行為と見なされます。

- 準備(洗浄、削り取り)が強調されていることは、**おもてなし(Omotenashi)**、すなわち無私の心によるもてなしの概念に繋がります。ごぼうをきれいにするのに必要な努力は、日本人がその最終的な味が努力を正当化することを知っているため、受け入れられる作業です。この物語は、一部の人々(または根菜)は評価されるためにより多くの手間を必要とするが、その手間もまた彼らの価値の一部であると示唆しています。

3. 土壌の重要性(大地と農業)

これら三つの根菜は、**和食(わしょく – 伝統的な日本料理)**、特に煮物やけんちん汁にとって不可欠です。物語が*地下*に設定されているという事実は、日本人と大地との深いつながりを強調しています。

この物語は、食料源とそれを栽培するために必要な努力に対する敬意を教えてくれます。野菜を擬人化することで、物語はそれらを単なる食材から尊厳ある登場人物へと高め、大地の恵みに対する感謝の念を促しています。これは、神道と日本を形作った農耕生活の核心的な教義の一つです。

パートIV:人間の本質の根源を考える

「にんじんとごぼうとだいこん」の物語は、時代や文化を超えて通用する、関連性があり強力な知恵の書として残っています。それは、簡潔で忘れられない教訓を提供します。

この物語の不変の真実とは、私たちの内面的な態度、すなわちプライド、嫉妬、そして恐怖は、決して完全に隠されることはないということです。それらは、不当に得た完璧さの外見として、生涯にわたる痛みを伴う修正として、あるいはしつこい冷たい不安の汗として、私たちの外面的な現実に現れるのです。

世界中の読者の皆様へ、にんじん、ごぼう、そしてだいこんの運命から、あなたは何を学び取りますか?

- **あなたの人生や現代社会において、どの根菜の欠点が最も共感できますか?** それはにんじんの表面的なプライドでしょうか、ごぼうの苦い嫉妬でしょうか、それともだいこんの麻痺させるような恐怖でしょうか?

- **もし、だいこんに話しかけることができるなら、彼の恐怖を克服するためにどのようなアドバイスをしますか?**

- **この物語は、あなたの食卓にある素朴な野菜を見る目を変えましたか?**

ぜひコメント欄であなたの考えを共有してください!この古代の知恵から、新たな深みを掘り起こす会話を始めましょう。

外部リンクと内部リンク

【内部カテゴリーリンク】

【外部参考リンク】

- 日本の食文化: 和食における根菜の役割(日本の料理と主要な食材のガイド。)

コメント