Meta Description: Discover how Japan’s unique view of religion and the afterlife blends ancestor worship, reincarnation, and cultural rituals in everyday life.

- On Japan’s “Ghost Day”: Unveiling the Japanese View of Religion and Life After Death

- Why Japanese Spirituality Seems Mysterious to the World

- “I’m Not Religious”—But Still Deeply Spiritual?

- Ancestor Worship: Japan’s Oldest Spiritual Bond

- Reincarnation and the Concept of Konpaku

- Religion in Everyday Life: Shinto, Buddhism, and Cultural Celebrations

- Death and Impermanence in Japanese Culture

- Quiet Spirituality: What It Means to Be ‘Non-Religious’ in Japan

- Conclusion: Rethinking Religion Through the Lens of Japanese Culture

On Japan’s “Ghost Day”: Unveiling the Japanese View of Religion and Life After Death

Every August, Japan quietly transforms. Homes glow with lanterns, temples resonate with ancient chants, and the spirits of the deceased are believed to return. This is Obon—often called “Ghost Day”—a time when the boundary between the living and the dead grows thin. And yet, ask a Japanese person if they’re religious, and many will say “no.”

This paradox has long puzzled international observers. How can a country so steeped in ritual and spiritual practices consider itself non-religious? To understand this, we must look beyond doctrine and dogma, and explore how Japan lives its spirituality—not in temples alone, but in the rhythm of daily life.

Why Japanese Spirituality Seems Mysterious to the World

For many in the West, religion is synonymous with belief systems, scriptures, and religious authorities. But Japan’s relationship with spirituality is different—subtle, ambient, and woven into customs rather than creeds. Visitors often find themselves surrounded by shrines, festivals, and spiritual symbols, and wonder: is this religious?

It’s easy to assume Japan is confusing or contradictory when viewed through a Western lens. But the answer lies in Japan’s historical and cultural evolution—a fusion of indigenous beliefs (Shinto), imported philosophies (Buddhism), and a shared reverence for nature and ancestors.

“I’m Not Religious”—But Still Deeply Spiritual?

The phrase “I’m not religious” is commonly heard in Japan. Yet this doesn’t signal atheism or apathy. Rather, it reflects Japan’s unique approach: a spiritual life that is largely untethered from institutionalized religion. People may not attend sermons or study religious texts, but they cleanse their hands at shrines, celebrate seasonal festivals, and pay respects at family graves.

This quiet spirituality is deeply emotional and personal. It’s found in the act of bowing before a shrine, offering food to a deceased relative, or pausing to appreciate the fleeting beauty of cherry blossoms. In Japan, spirituality is an everyday presence—quiet, respectful, and deeply felt.

Ancestor Worship: Japan’s Oldest Spiritual Bond

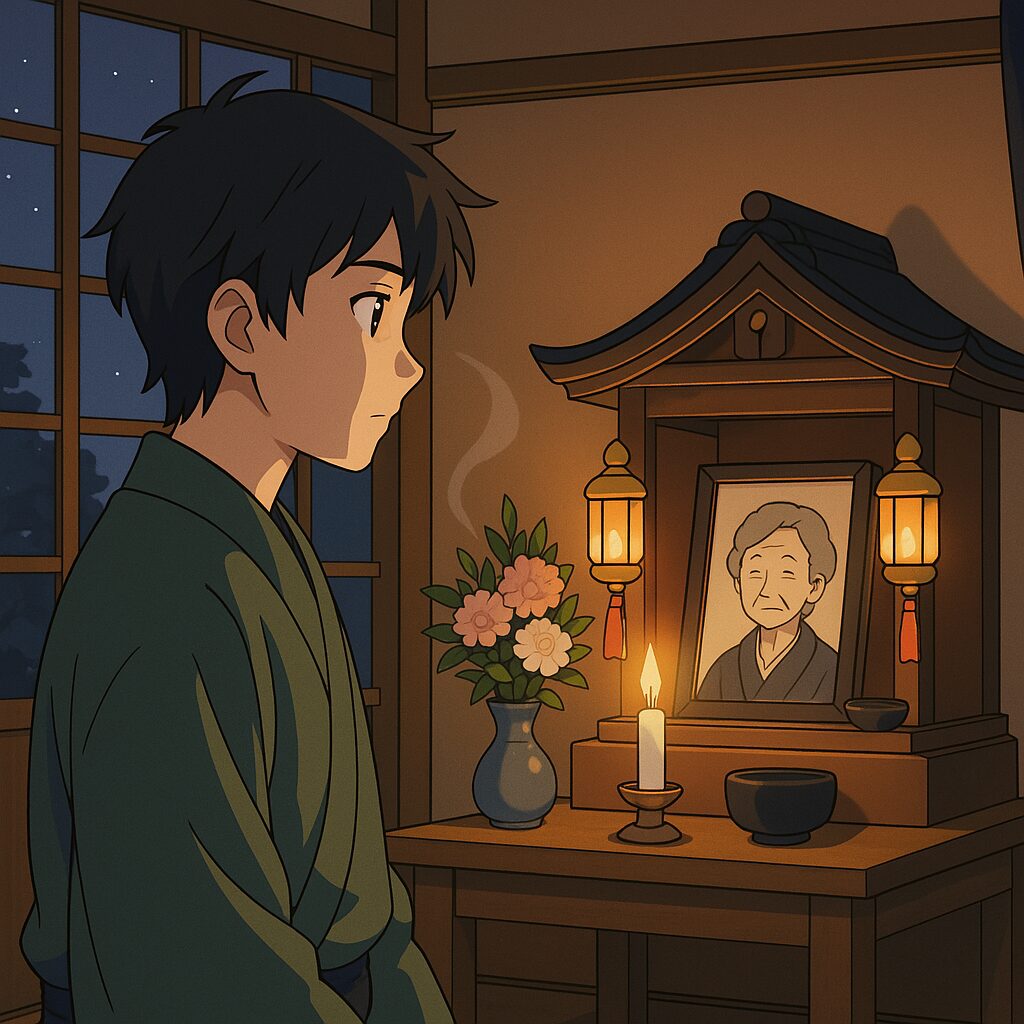

Central to Japanese spirituality is the bond with one’s ancestors. Families maintain household altars (kamidana or butsudan), burn incense at gravesites, and offer symbolic gifts of food, drink, or flowers. These gestures reflect an ongoing relationship—not just memory, but dialogue—with the departed.

The idea isn’t that death separates us entirely, but rather transforms the way we relate. Ancestors are revered, consulted, and honored—not just once a year, but continuously. This ancestral connection transcends religion and speaks to Japan’s core values of respect, harmony, and continuity.

Reincarnation and the Concept of Konpaku

Buddhism brought with it beliefs in reincarnation, karmic cycles, and spiritual progression. Yet indigenous concepts like konpaku—the idea of the soul’s duality, with one part staying in the world and another departing—remain influential. Japanese folklore brims with ghost tales, yūrei (restless spirits), and supernatural beings that embody cultural anxieties, hopes, and lessons.

Spirituality in Japan isn’t confined to temples—it lives in stories, art, seasonal customs, and even the way society handles grief and memory.

Religion in Everyday Life: Shinto, Buddhism, and Cultural Celebrations

Unlike Western religious practices that often require choosing one faith, Japanese people freely participate in both Shinto and Buddhist customs. A birth may be celebrated at a Shinto shrine, a wedding conducted in Christian fashion, and a funeral in Buddhist tradition—without contradiction.

This fluidity reflects Japan’s pluralistic spirit. Festivals like Setsubun, Tanabata, and New Year shrine visits aren’t just cultural—they’re spiritual acts. They connect individuals to nature, ancestors, and the community in profound yet understated ways.

Death and Impermanence in Japanese Culture

The concept of mono no aware—a sensitivity to impermanence—is central to Japanese thought. It teaches that all things are transient, and that beauty lies in their fleeting nature. From falling cherry blossoms to the fading summer cicadas, Japanese aesthetics celebrate the bittersweet ephemerality of life.

This reverence for impermanence shapes spiritual attitudes toward death. Rather than being feared or denied, death is accepted as a natural transition, a part of the ongoing cycle of existence.

Quiet Spirituality: What It Means to Be ‘Non-Religious’ in Japan

In Japan, spirituality isn’t defined by sermons or theological debates—it’s lived quietly, respectfully, and often symbolically. A child placing fruit before a family altar, a commuter bowing at a roadside shrine, or a grandmother lighting incense on Obon night—these are spiritual moments, profound in their simplicity.

This form of spirituality can be difficult to categorize, but it’s deeply meaningful. It fosters empathy, gratitude, and connection—values that transcend language and belief.

Conclusion: Rethinking Religion Through the Lens of Japanese Culture

Japanese spirituality challenges global definitions of religion. It reminds us that faith isn’t always loud or doctrinal—it can be humble, inherited, and embedded in rituals that span generations. In Japan, spiritual life is a fabric of reverence, rhythm, and respect—not bound by creeds, but illuminated by moments.

Perhaps in understanding Japan’s quiet spirituality, we expand our own sense of what it means to live a sacred life.

コメント